Insights and Stories from Sapa and the Northern Borderbelt provinces of Vietnam.

The Heart of Hmong Batik: A Living Tradition

Discover the artistry and cultural depth of Hmong batik in Sapa with ETHOS. Our immersive workshops guide you through the wax-drawing process, indigo dyeing and the centuries-old meanings woven into every motif, offering a respectful and sensory journey into this living textile tradition.

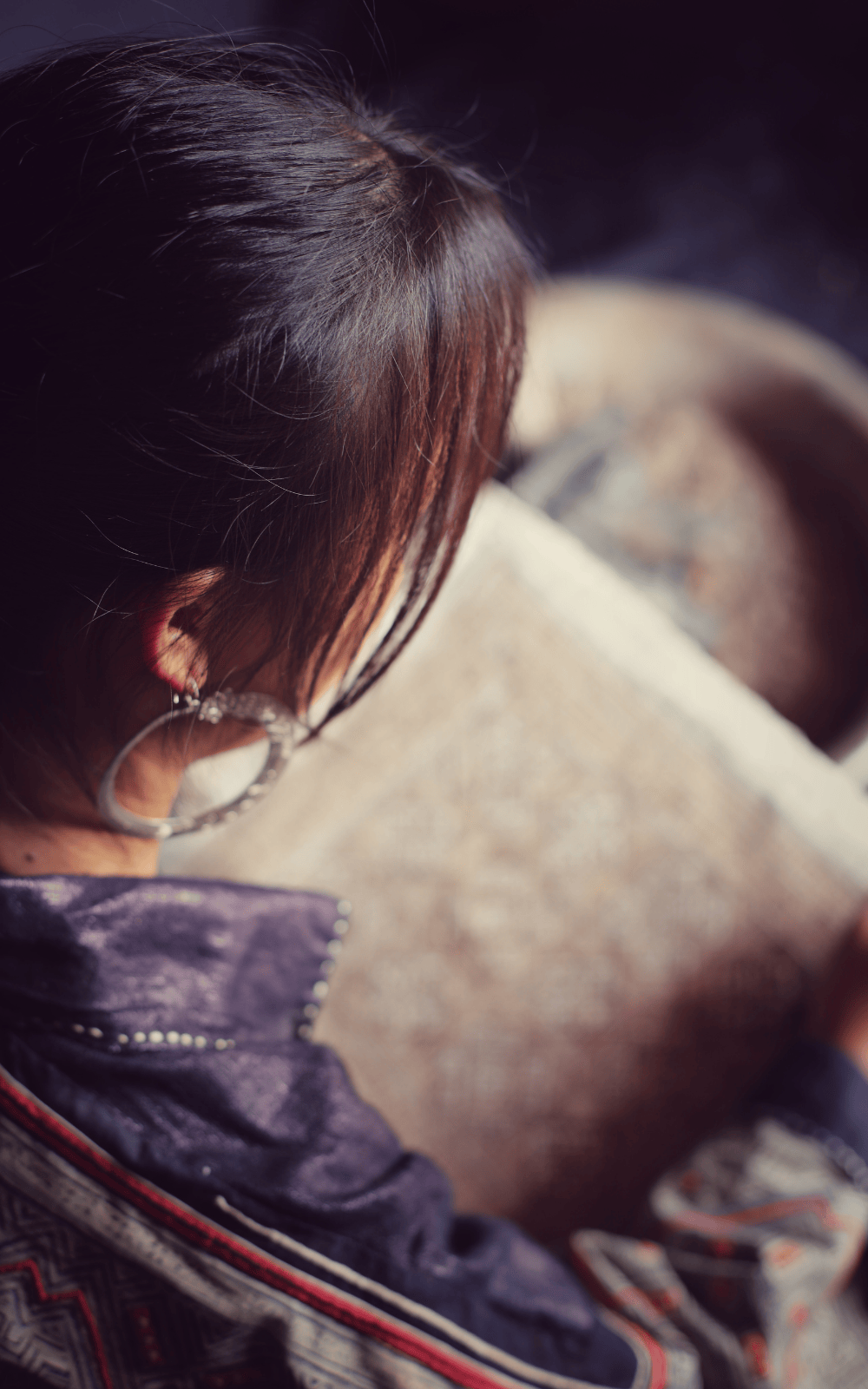

In Sapa, north-western Vietnam, batik is a traditional craft and a way of seeing the world and telling stories without words. In our workshops, hosted in the ETHOS community centre by skilled Hmong artisans, you are invited to slow down and meet this textile tradition from the inside, learning not just techniques but the cultural logic that sustains them.

Batik here begins with the material itself. Traditionally, Hmong cloth was made from hand-processed hemp, a hardy fibre harvested from the fields and beaten until soft and ready for weaving. While commercial fabrics are sometimes used elsewhere today, the spirit of making cloth by hand remains integral, grounding the craft in land, labour and lineage. At ETHOS, our workshops use only traditional tools and materials, which means every batik piece is created on hand-spun, hand-woven hemp cloth.

The Batik Workshop Experience: Process, Story and Sensory Learning

From the moment you step into the workshop space, the rhythm of the day is deliberate and tactile. You begin by peeling and twisting hemp fibres before beeswax is melted slowly over low heat. You watch its pale gold colour transform into a flowing liquid medium. Using a traditional batik tool, with a bamboo handle and copper-tipped, you draw directly onto the cloth, learning how to balance heat, line and intention. The wax resists the dye that will come later, preserving the patterns you create.

As you work, your artisan guide shares the stories behind the motifs. Geometric steps may speak of mountain paths, spirals can echo seed and storm, and borders often hold ideas of protection and balance. The symbolism woven into these forms is not fixed but conversational, rooted in community memory and personal interpretation.

After pausing for a simple, home-style lunch and conversation around the table, you move to the indigo vat. This deep blue dye is made from local indigo leaves that have been fermented and carefully tended in earthen jars. Cloth is dipped again and again, lifted into the air where the blue slowly deepens as it meets oxygen. With each immersion, a rhythm emerges that teaches patience, attention and presence.

Throughout the day, the workshop is as much about listening as it is about doing. You hear why certain motifs appear again and again, how batik once served as a coded form of expression in a culture without written language, and how textile arts continue to connect makers across generations.

By the time you stand back and see your own batik panel in indigo and white, you are holding more than cloth. You have touched a tradition that still shapes identity in Sapa and beyond. You have witnessed the interplay of craft and community, of maker and material. You carry with you not just a piece of fabric, but an understanding of why these patterns still matter and why they continue to speak across cultures.

A Note on Imitations and Responsible Travel

As interest in batik grows, so too do imitations. Many short workshops now offered in tourist centres use machine-made, bleached fabrics and chemical dyes to produce quick results. While these experiences may look similar on the surface, they are not authentic representations of Hmong batik practice.

More importantly, such shortcuts undermine the true process and its environmental balance. Chemical dye vats are often emptied directly into local rivers and streams, causing long-term harm to water systems that farming communities depend on. These practices also disconnect batik from its cultural roots, turning a living tradition into a disposable activity.

We encourage travellers to look carefully at how and where they choose to learn. Authentic batik is slow, labour-intensive and deeply connected to place. When practised responsibly, it supports local artisans, preserves cultural knowledge and respects the land that sustains it. Travellers beware, and travellers be curious. The difference is not always obvious at first glance, but it matters deeply.

Experience This With ETHOS

Join our ethical trekking tours in Sapa

Stay in authentic Hmong homestays

Discover Sapa’s culture with our workshops