Insights and Stories from Sapa and the Northern Borderbelt provinces of Vietnam.

Red Dao New Year in Sapa: Rituals, Feasts and Traditional Dress at Tết

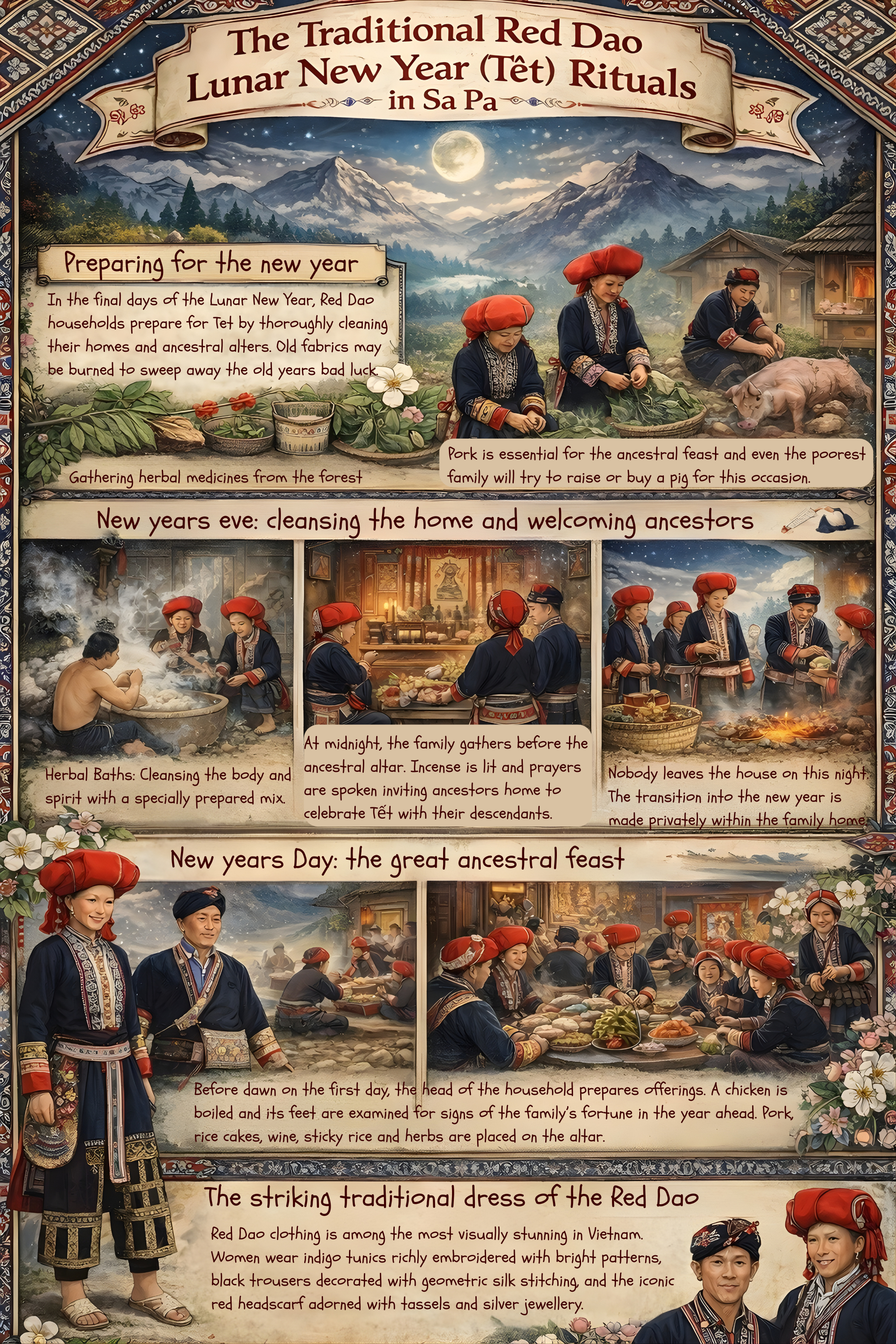

In the mountains around Sapa, the Red Dao welcome Tết with herbal baths, solemn ancestor worship, generous village feasts and the spectacular fire jumping ceremony. It is a New Year shaped by memory, spirit and striking traditional dress.

Lunar New Year is a deeply spiritual season for the Red Dao people of Sapa. It is a time when the household is spiritually renewed, ancestors are invited home, and the whole villages move through a sequence of rituals that blend belief, family life and celebration.

These days, the Red Dao share the same lunar calendar as the rest of Vietnam, but their customs during Tết are distinctive. Herbal cleansing baths, unique humpback shaped rice cakes, elaborate ancestral offerings and communal feasting all form part of a New Year that is both traditional and joyful.

Preparing for the New Year

Traditional Tết offerings prepared for the Red Dao ancestral altar, including a boiled chicken, sliced pork and ritual foods arranged on banana leaves.

Red Dao boys wearing indigo traditional clothing with embroidered detail, preparing for the New Year celebrations in a mountain village in Sapa.

Hands wrapping bánh chưng gù, the Red Dao humpback sticky rice cake, in forest leaves as part of New Year food preparations.

Preparations begin well before the last day of the lunar year. Homes are thoroughly cleaned, especially the ancestral altar. Red paper cuttings and handmade votive paper are placed around the altar to protect the household from misfortune and invite good luck.

Food preparation is central to this period. Pork is essential for ancestral offerings, and families ensure they have a pig ready for the celebrations. Women lead the making of the Red Dao’s distinctive Tet cake, bánh chưng gù, a small humpback shaped sticky rice cake wrapped in forest leaves. At the same time, women and girls finish embroidery on traditional clothing so that everyone will be properly dressed for the new year.

Everything must be ready before New Year’s Eve because once the new year begins, it is believed that opening cupboards, lending objects or cleaning the house risks losing good fortune.

New Year’s Eve: Herbal Cleansing and Quiet Reflection

On the afternoon of New Year’s Eve, the Red Dao carry out one of their most recognisable rituals. Forest herbs are boiled to create a medicinal bath. Each member of the family washes in this herbal water to remove the old year’s bad luck and prepare spiritually for the new one.

After bathing, everyone dresses in full traditional clothing. The evening is calm and reflective. Families remain inside their homes as midnight approaches.

Midnight: Welcoming the Ancestors Home

At midnight, the family gathers before the ancestral altar. Offerings of pork, chicken, rice cakes, wine and incense are laid out carefully. The head of the household lights incense and recites prayers to invite the ancestors to return home to celebrate Tết with their descendants.

A bowl of blessed water is shared among family members for health and protection in the coming year. Nobody leaves the house during this sacred transition from one year to the next.

Dawn of the First Day: Signs of Fortune

At dawn, family members step outside to collect a fresh green branch which symbolises spring and renewal. A chicken is boiled and its feet are examined carefully. The appearance of the claws is believed to foretell the family’s fortune in the year ahead.

The Great Ancestral Offering and First Feast

The largest ancestral offering of the year is then presented. A pig’s head, chicken, bánh chưng gù, sticky rice, wine and other dishes are placed on the altar. Prayers ask for health, good harvests and prosperity.

After the ceremony, the offerings are taken down and shared as the first meal of the year. Relatives, neighbours and friends are invited to join. The Red Dao believe that a crowded house on the first day brings good fortune, so the celebration often moves from house to house across the village.

A multi-generational Red Dao family sharing a festive meal. The setting feels intimate and celebratory, reflecting the first communal feast of the New Year.

Three Red Dao women wearing embroidered clothing sit together at a table covered with home-cooked dishes. They smile warmly in a dimly lit wooden interior, with bowls of soup, meat, and herbs arranged in front of them, capturing a moment of hospitality and shared celebration during the New Year meal.

Tết Nhảy: The Fire Jumping Ceremony

One of the most extraordinary elements of Red Dao New Year is Tết Nhảy, also known as Pút Tồng. This clan ceremony combines ritual dance, music and a dramatic fire jumping performance.

Led by a shaman, young men perform a series of sacred dances to invite the ancestors and gods to join the celebration. The ceremony builds towards the fire dance, where participants lift flaming papers and leap barefoot across glowing embers. This act symbolises courage, purification and the burning away of bad luck.

Tết Nhảy is recognised as an important element of Red Dao cultural heritage and different to that of the Hmong or in other Vietnamese New Year traditions.

Red Dao man dancing on embers in a family home.

Songs, Games and Teaching the Dao Script

Beyond rituals, the New Year is also a social and educational season. Elders use the first days of the year to teach children the ancient Dao characters and share stories about their ancestors.

The Striking Traditional Dress of the Red Dao

Traditional clothing is an essential part of Tết. Women wear indigo tunics richly embroidered with bright patterns, black trousers decorated with geometric stitching, and the iconic red headscarf with tassels and silver jewellery. Men wear indigo jackets with red accents and headscarves.

Wearing traditional dress honours the ancestors, expresses cultural pride and is believed to bring good luck for the year ahead.

A young Red Dao girl wearing an indigo embroidered tunic and decorative collar, dressed in traditional clothing for the New Year in Sapa.

An elderly Red Dao woman wearing the iconic red headscarf, indigo tunic and embroidered panels that symbolise cultural identity and heritage.

A Red Dao child in traditional indigo clothing with colourful embroidered trim, dressed for Tết celebrations in a mountain village.

A New Year Rooted in Memory and Identity

For the Red Dao of Sapa, Tết is a celebration, the renewal of family ties, spiritual belief and cultural identity carried forward from one generation to the next. Through ritual, food, clothing and community, the Red Dao step together into the new year with hope and deep respect for their past.

Join our ethical Red Dao treks in Sapa

Stay in authentic Dao homestays

Discover more about Dao culture with our workshops

Black Hmong New Year in Sapa: Ritual, Renewal and Indigo Identity

In the mountains around Sapa, the Black Hmong New Year renews both spirit and community. Through shamanic soul-calling rites, offerings, pav tuav, rice wine, festivals and indigo hemp clothing, the celebration binds people to land, ancestors and one another.

In the highlands surrounding Sapa, the Black Hmong New Year is a period when daily life pauses and the relationship between people, spirits, animals and land is renewed. Following the harvest, tools are put away and attention turns first to the household, then outward to the village through festival, music and play. This is a spiritual reset expressed through ritual, food, clothing, music and social life. While many families today align celebrations with Vietnam’s national Tết for practical reasons, the Black Hmong observances remain deeply rooted in their own cosmology.

The Rhythm of the Celebration

Traditionally, the New Year begins once agricultural work is complete. Homes are cleaned. Clothing is finished. Food is prepared. Rice wine is distilled in advance for ritual and visiting. For days afterwards, families visit relatives, exchange blessings and attend communal gatherings filled with games, music and courtship. Normal labour is suspended so that attention can be given to relationships, spirit and renewal. These days, Hmong New Year is more aligned with the Vietnamese Tet celebrations, but Hmong rituals remain unique.

The Household as Sacred Space

The earliest moments of the New Year are domestic and spiritual. The ancestral altar is carefully prepared. Incense is lit. Offerings are made to ancestors and household spirits. A pig is often central to these rites, first presented in prayer before becoming part of the shared meal. The fire symbolises continuity and protection. The house becomes the place where the old year is formally closed and the new one welcomed through ritual order.

Shamanism and Spiritual Renewal

At the centre of Black Hmong spirituality stands the txiv neeb, the master of spirits. Hmong religion is traditionally animist, grounded in belief in the spirit world and in the interconnectedness of all living things. The human body is believed to host multiple souls. When one or more become separated, illness, depression or misfortune can follow. Healing rites are therefore known as soul-calling rituals, because the lost soul must return.

New Year is a powerful moment for this work.

Soul-calling and the journey to the spirit world

During a séance, the shaman is transported to the spirit world by means of a ‘flying horse’, a narrow wooden bench that serves as spiritual transport. Wearing a paper mask, which blocks out the real world and disguises the shaman from hostile spirits, the shaman enters trance.

Assistants steady the shaman as he mounts the bench. It is believed that if the shaman falls before his soul returns, he will die. In this state, the shaman’s soul leaves the body and enters the spirit realm where he can see, speak to, touch and capture spirits in order to liberate lost human souls.

Shamanic language is used throughout, blending everyday Hmong with the ritual dialect Lus Suav or Mon Draa. The chanting invites the too Xeeb spirit to manifest, accept offerings and grant blessings.

Divination, gong and sacrifice

As the shaman chants, he throws the Kuaj Neeb, two halves of a buffalo horn used for divination. Their landing position reveals whether spirits accept the offerings. He also strikes the Nruag Neeb, a small metal gong whose reverberation is believed to amplify spiritual strength and protect him. Villagers may pool money to buy a large sacrificial pig as a collective offering for the entire community. In Hmong belief, the soul of the animal can support or protect human souls. The sacrifice is understood as life given to restore life. Young men prepare and cook the meat while women cook rice. Rhythmic dances take place in same sex groups, each dancer holding a gong and moving barefoot before the altar.

Bamboo papers are laid in a line before participants. The shaman chants over each person, uses the buffalo horns for divination, then the papers are burned and their ashes read to assess spiritual health and predict future séances.

Fire, trance and communal feast

A pyre is built from old ritual papers. As chanting intensifies and gongs grow louder, the shaman rolls through the embers, sending sparks into the air. Others follow, dancing through smoke with stamping feet. Bowls of meat and rice are placed on the altar with cups of distilled rice wine. Food and drink are offered to the spirits before the communal feast begins. The ceremony ends in shared eating, storytelling and laughter long into the night.

New Year Food and Hospitality

Food during New Year signals abundance and generosity. Pork dominate festive meals, often from animals first used in ritual offering. Sticky rice cakes known in Hmong as pav tuav are made by pounding glutinous rice into smooth rounds, sometimes in friendly competitions.

Distilled rice wine is essential. It is used in ritual, offered to spirits and shared with guests. Accepting a cup is part of accepting the relationship and blessing.

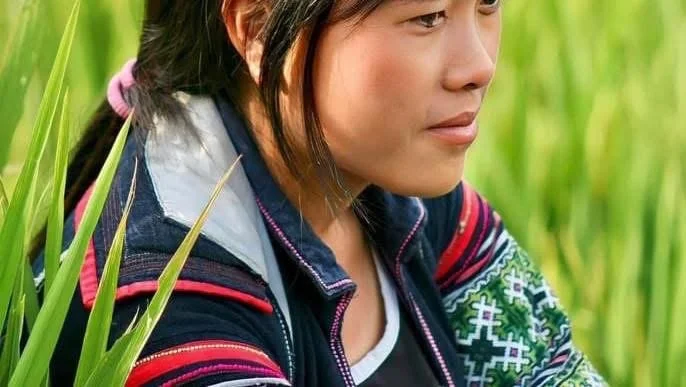

Clothing: Hemp, Indigo and Identity

New Year is visually striking because everyone wears new or newly finished clothing. This symbolises renewal and showcases months of labour in hemp weaving, indigo dyeing, batik and embroidery.

Hemp at the heart of Black Hmong textile life

Hemp has long been central to Black Hmong textile traditions in Sapa. It is valued not only as a fibre but for its cultural and spiritual meaning. Hemp grows well in the cool, humid highlands and is cultivated in family plots. After harvesting, stalks are retted in water, fibres stripped, dried and beaten, then hand-spun into thread. The thread is woven on backstrap looms into sturdy, breathable cloth. This process can take many months and knowledge is passed primarily through women. The cloth is dyed repeatedly in natural indigo baths to achieve the deep blue-black colour associated with Black Hmong clothing. Patterns are created using beeswax batik or intricate silk embroidery, often taking many more months. Motifs represent daily life, nature and important milestones.

Spiritual meaning of hemp

Hemp is not only worn in life but is central in death. In Hmong funerals, a hemp shroud traditionally wraps the deceased. This is a spiritual necessity. It is believed that only hemp can guide the soul safely back to the ancestral realm. Without hemp, the soul may become lost. This belief ties hemp directly to cosmology and the journey between worlds. For the Black Hmong, hemp symbolises resilience, continuity and identity. It connects people to land, ancestors and tradition even as modern fabrics become available.

Indigo clothing at New Year

Women’s indigo garments, decorated with batik and embroidery, are paired with silver jewellery. Men’s clothing is simpler but still formal. Children wear miniature versions. New Year becomes a community exhibition of textile skill and cultural pride.

Festivals, Games and Courtship

After household rites, attention turns to communal gatherings such as the Gau Tao festival. A tall decorated bamboo pole is erected, prayers are made, and the area becomes a place of games, music and social life.

Bamboo wrestling, stilt walking, spinning tops, crossbow contests and tug-of-war take place alongside ném pao, the ball-toss game where young men and women meet, talk and flirt.

Taboos and Beginning the Year Well

Before the New Year, the Hmong cut three bamboo sticks and wrap them with red cloth. These are then used to sweep away spider webs and black soot from the house. This act symbolises clearing away the old year and preparing for a fresh beginning.

During the first days of the New Year, certain actions are avoided. People avoid washing clothes, blowing on the fire, eating rice with water, or holding a needle. Each of these actions carries meaning. Washing clothes is believed to wash away the blessings of the ancestors. Eating rice with water suggests a life of rain and hardship. Blowing on the fire may bring strong winds throughout the year. Sewing or using a needle symbolises damage to the crops, especially the maize harvest.

On the 19th day of the twelfth lunar month, which marks the Hmong New Year, families prepare sticky rice cakes and offer them to their ancestors. The cakes must not be eaten before the prayers are completed. It is believed that if someone eats before the ritual is finished, they may suffer burns from fire or hot charcoal during the coming year. This teaches patience and respect, reminding everyone that the ancestors must be honoured first.

These practices show how deeply the New Year is connected to spiritual protection, family unity and the guidance of those who came before.

A Living Tradition in Modern Sapa

Modern life has influenced the timing and visibility of the celebration, yet the core remains intact. Ancestors are honoured. Shamans chant. New clothes are made. Rice wine is poured. Young people meet in games and song. Each year, when winter turns to spring in the mountains around Sapa, the Black Hmong step into a new cycle with rituals that bind body, soul, family and village into one shared renewal.

Mastering Mountain Trails: Demystifying Trekking Difficulty in Sapa

Most Sapa treks follow the same crowded paths. This guide explains what trekking difficulty really means in the mountains and how small group, ethical routes offer a more rewarding experience for travellers and local communities alike.

Why Most Sapa Treks Feel the Same

A large mixed group of tourists walking together with local women along a wide path near a village entrance in Sapa, illustrating the busy, organised nature of mainstream trekking routes in popular tourist areas.

Several trekking groups following the same concrete path through the Muong Hoa Valley, showing how visitors are funnelled along identical routes regardless of ability, weather, or experience.

A steady line of tourists crossing a narrow bamboo bridge towards a purpose built café area in Cat Cat Village, highlighting the commercial, crowded feel of copy book tourism in Sapa’s most visited locations.

If you search for a trek in Sapa, you will quickly notice the same village names appearing again and again; Cat Cat, Lao Chai and Ta Van.

These are the routes most travellers are sold in Hanoi by third party agents. They are easy to organise, simple to market, and predictable for tour companies. Every morning, dozens of small groups leave Sapa town at roughly the same time and follow almost identical paths into the Muong Hoa Valley.

On paper, this sounds idyllic. Rice terraces, minority villages, waterfalls, bamboo bridges. In reality, it often becomes a slow procession of tourists walking the same concrete paths and village roads. Lunch is taken in large restaurants built to serve volume. Homestays are often purpose built guesthouses that can sleep twenty or more people at a time. The difficulty of the trek is not designed around you. It is designed around the least prepared person in a large group. The “treks” are identical to the day before and the same as all the other tour groups.

What “Trekking Difficulty” Really Means in the Mountains

When travellers ask how difficult a Sapa trek is, they usually mean distance. Five kilometres. Ten kilometres. Twelve kilometres. In the mountains, distance tells you very little.

Trekking difficulty here depends on elevation gain, recent weather, the condition of the paths, and how confident you feel walking along narrow earthen paddy walls above steep terraces. It depends on whether you are climbing through dense bamboo forest or following a concrete track between villages. Most group tours cannot adapt to these factors. The guide must keep the group together. The route cannot change because transport, lunch stops, and accommodation are pre arranged. Even if the path becomes slippery after rain, the group still follows the same way.

This is why many travellers finish their trek feeling either under challenged or completely exhausted.

A Different Way to Trek with ETHOS – Spirit of the Community

Travellers walking quietly through vibrant rice terraces on a narrow earthen path, far from roads and crowds, illustrating the calm and personal nature of small group trekking in remote parts of Sapa.

A local Hmong guide helping travellers cross a shallow mountain stream, showing hands on guidance, adaptable routes, and the close support that comes with private, community led trekking.

A traveller sharing a meal inside a local family home with a host, highlighting the genuine homestay experience made possible by small groups and strong relationships with village families.

There is another way to experience these mountains. With ETHOS, treks are designed for solo travellers, couples, and families in groups of no more than five. Often it is just you and your guide. This changes everything.

Your guide is a Hmong or Dao woman walking trails she uses in daily life. She is a farmer, a mother, a craftswoman, and a community leader. She watches how you move. She notices when you are comfortable and when you are not. Routes are adjusted as you walk. If the ground is too slippery, the path changes. If you are feeling strong, the trek can be extended along a higher ridge with bigger views. If you want a gentler pace, you can follow quieter valley paths between small hamlets rarely visited by tourists. Trekking difficulty becomes something flexible and personal, not fixed and generic.

Why Small Groups Create Better Experiences for Everyone

Small groups do not just improve the experience for visitors. They transform the experience for guides and host families too. Because routes are not fixed, ETHOS guides can reach many different villages across the region. Lunch is taken in real homes, not roadside restaurants. Overnight stays happen in genuine family houses, not large homestay businesses built for tour groups. This spreads tourism income across a wider network of families. It reduces pressure on the few villages that have become overwhelmed by mass tourism. It allows guides to share their own home villages, their own stories, and their own knowledge of the land.

For travellers, this means meals cooked over open fires, conversations through translation and laughter, and a far deeper understanding of daily life in the mountains.

Choosing the Right Trek for Your Ability

Travellers walking through remote rice fields with an ETHOS guide on a narrow path, showing the quiet, immersive nature of trekking away from main roads and tourist routes.

A small group pausing on a hillside as their ETHOS guide explains the landscape below, illustrating how routes and pace are shaped by conversation, observation, and personal ability.

Travellers navigating a dense bamboo forest trail with their guide, highlighting the more adventurous terrain and varied conditions that define moderate to challenging treks in Sapa.

With ETHOS, treks are described as easy, moderate, or moderate to challenging. These are not marketing labels but starting points for a conversation. An easy trek may still include uneven ground and narrow paths, but with less elevation gain and more time in villages. A moderate trek may involve sustained climbs, bamboo forest sections, and paddy wall crossings. A challenging route might include long ascents to high viewpoints and remote hamlets far from roads. The key difference is that you are not locked into one option. You can adapt as you go.

This is what trekking in Sapa should feel like. Responsive. Human. Grounded in the landscape rather than restricted by a timetable.

Trekking That Supports Communities, Not Just Tourism

Every ETHOS trek supports fair wages, skills training, health insurance, and long term opportunities for local women guides. It also supports village clean ups, education projects, and community initiatives that reach far beyond tourism.

When you walk these trails, you are not simply passing through a beautiful landscape. You are participating in a model of travel that values people, culture, and environment equally.

Rethinking What a “Sapa Trek” Should Be

If your idea of trekking in Sapa is following a line of tourists down a concrete path to a busy village café, then the standard routes will suit you. If you want to feel the earth beneath your boots, hear stories beside a cooking fire, and adjust your day based on how the mountain feels under your feet, then a small group, ethical trek offers something entirely different.

Trekking difficulty in Sapa is not about kilometres, but more about how deeply you wish to step into the landscape and the lives of the people who call it home.

Travellers following their ETHOS guide along a narrow forest trail beside a waterfall, showing the kind of off path terrain and natural surroundings reached on quieter, less travelled routes.

A small group walking single file through tall rice terraces on a narrow earthen ridge, illustrating immersive trekking through working farmland far from roads and tourist traffic.

An ETHOS guide leading a family across a simple bamboo fence between terraced fields, highlighting how these routes pass through everyday village life rather than purpose built tourist areas.

Join our ethical trekking tours in Sapa

Stay in authentic Dao and Hmong homestays

Discover Sapa’s culture with our workshops

The Heart of Hmong Batik: A Living Tradition

Discover the artistry and cultural depth of Hmong batik in Sapa with ETHOS. Our immersive workshops guide you through the wax-drawing process, indigo dyeing and the centuries-old meanings woven into every motif, offering a respectful and sensory journey into this living textile tradition.

In Sapa, north-western Vietnam, batik is a traditional craft and a way of seeing the world and telling stories without words. In our workshops, hosted in the ETHOS community centre by skilled Hmong artisans, you are invited to slow down and meet this textile tradition from the inside, learning not just techniques but the cultural logic that sustains them.

Batik here begins with the material itself. Traditionally, Hmong cloth was made from hand-processed hemp, a hardy fibre harvested from the fields and beaten until soft and ready for weaving. While commercial fabrics are sometimes used elsewhere today, the spirit of making cloth by hand remains integral, grounding the craft in land, labour and lineage. At ETHOS, our workshops use only traditional tools and materials, which means every batik piece is created on hand-spun, hand-woven hemp cloth.

The Batik Workshop Experience: Process, Story and Sensory Learning

From the moment you step into the workshop space, the rhythm of the day is deliberate and tactile. You begin by peeling and twisting hemp fibres before beeswax is melted slowly over low heat. You watch its pale gold colour transform into a flowing liquid medium. Using a traditional batik tool, with a bamboo handle and copper-tipped, you draw directly onto the cloth, learning how to balance heat, line and intention. The wax resists the dye that will come later, preserving the patterns you create.

As you work, your artisan guide shares the stories behind the motifs. Geometric steps may speak of mountain paths, spirals can echo seed and storm, and borders often hold ideas of protection and balance. The symbolism woven into these forms is not fixed but conversational, rooted in community memory and personal interpretation.

After pausing for a simple, home-style lunch and conversation around the table, you move to the indigo vat. This deep blue dye is made from local indigo leaves that have been fermented and carefully tended in earthen jars. Cloth is dipped again and again, lifted into the air where the blue slowly deepens as it meets oxygen. With each immersion, a rhythm emerges that teaches patience, attention and presence.

Throughout the day, the workshop is as much about listening as it is about doing. You hear why certain motifs appear again and again, how batik once served as a coded form of expression in a culture without written language, and how textile arts continue to connect makers across generations.

By the time you stand back and see your own batik panel in indigo and white, you are holding more than cloth. You have touched a tradition that still shapes identity in Sapa and beyond. You have witnessed the interplay of craft and community, of maker and material. You carry with you not just a piece of fabric, but an understanding of why these patterns still matter and why they continue to speak across cultures.

A Note on Imitations and Responsible Travel

As interest in batik grows, so too do imitations. Many short workshops now offered in tourist centres use machine-made, bleached fabrics and chemical dyes to produce quick results. While these experiences may look similar on the surface, they are not authentic representations of Hmong batik practice.

More importantly, such shortcuts undermine the true process and its environmental balance. Chemical dye vats are often emptied directly into local rivers and streams, causing long-term harm to water systems that farming communities depend on. These practices also disconnect batik from its cultural roots, turning a living tradition into a disposable activity.

We encourage travellers to look carefully at how and where they choose to learn. Authentic batik is slow, labour-intensive and deeply connected to place. When practised responsibly, it supports local artisans, preserves cultural knowledge and respects the land that sustains it. Travellers beware, and travellers be curious. The difference is not always obvious at first glance, but it matters deeply.

Experience This With ETHOS

Join our ethical trekking tours in Sapa

Stay in authentic Hmong homestays

Discover Sapa’s culture with our workshops

The Cultural Threads of Hmong Hemp Weaving

For the Hmong people of northern Vietnam hemp weaving is a craft and a living tradition that celebrates culture, family and the enduring connection between people and nature.

A Living Tradition

Hemp, or Cannabis sativa, has long been a valuable fibre cultivated by the Hmong people in the mountains of northern Vietnam. For generations, it has been used to make clothing that reflects both identity and artistry.

Hmong women take great pride in their handmade garments, especially the beautifully pleated hemp skirts worn during festivals, weddings and market days. Each piece represents weeks of work and a deep understanding of the land. The process of growing, harvesting and weaving hemp connects families to their heritage and to the natural world that sustains them.

Symbolism and Cultural Meaning

Hemp holds an important place in Hmong life beyond its practical use. At funerals, the deceased are dressed in hemp clothing, with women traditionally wearing four skirts. Family members and guests also wear hemp attire as a sign of respect.

Children often prepare hemp garments for their parents in advance, a gesture of love and duty. Hemp cloth is also used in spiritual worship and as part of wedding gifts. A bride is expected to wear a hemp skirt made by her mother-in-law, symbolising unity, respect and the joining of families.

From Seed to Cloth

Many Hmong subgroups across Vietnam’s highlands grow hemp, keeping alive a tradition that is both sustainable and culturally rich. Producing hemp cloth takes around seven months and involves detailed, physical work.

The hemp is sown in early May following age-old customs believed to encourage strong growth. After about two and a half months, the plants are harvested and the stalks are dried before being stripped for fibre. The long process of connecting and spinning the fibres produces strong, smooth threads, which are then woven into fabric on simple wooden looms.

The final cloth is washed and pressed many times to achieve a soft, smooth texture. Each finished piece tells a story of patience, craftsmanship and connection to nature.

Preserving Cultural Heritage

Hemp weaving continues to represent more than just a craft for the Hmong. It is a symbol of cultural resilience, sustainability and identity. Every strand spun and woven carries the memory of generations who have kept these traditions alive through care and dedication.

Hemp Workshops

ETHOS - Spirit of the Community work with local Hmong artisans to create hemp based workshops. Please see our website for more information.

Experience This With ETHOS

Join our ethical trekking tours in Sapa

Stay in authentic Hmong homestays

Discover Sapa’s culture with our workshops

When Good Intentions Aren’t Enough: Child Sellers in Sapa and Ha Giang

In Sapa and along the Ha Giang Loop, children selling souvenirs or offering treks can be a confronting sight for travellers. While often well-intentioned, buying from children keeps them out of school and at risk. This post explores the deeper realities behind child selling and how ethical, community-led tourism can create safer, more meaningful livelihoods for families in northern Vietnam.

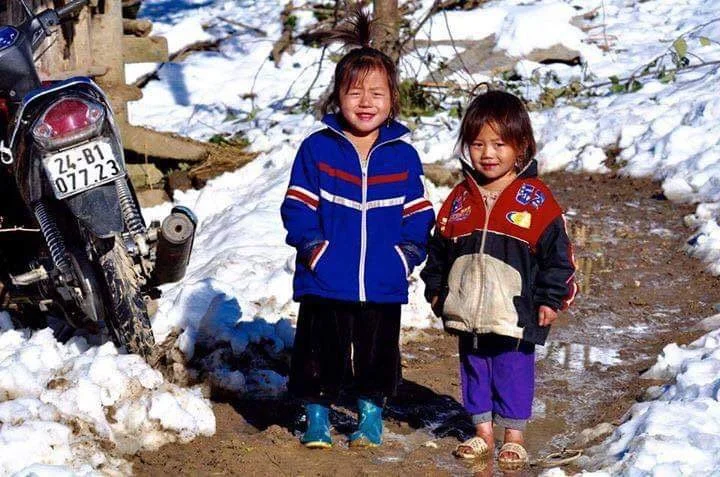

As you wander the streets of Sapa, children may approach you with bright smiles and outstretched hands, offering embroidered bracelets, posing for photographs, or inviting you to trek to their village. In Ha Giang, you might see children waiting patiently at mountain viewpoints, dressed in traditional clothing, ready for a photo in exchange for money.

For many travellers, these encounters feel human and heartfelt. Some feel joy at the connection, others a sense of responsibility to help. But behind these moments lies a far more complex reality, one that deserves careful thought.

At ETHOS, we believe that ethical travel begins with understanding. This post is a request: not to photograph children in exchange for money, not to give gifts or sweets to children, and not to buy tours or products from minors. It is also a call to support adult-led, community-based tourism that genuinely strengthens local livelihoods.

The Reality Behind Child Selling

Children selling souvenirs or offering treks are not simply being “enterprising”. Their presence on the streets is often driven by poverty, limited adult employment, and long-standing marginalisation of ethnic minority communities.

While education in Sapa is free up to grade nine, many street-selling children attend school exhausted after long nights working, or miss classes entirely. Money earned today can easily outweigh the promise of future opportunity, especially when families struggle to buy food, clothing, or winter supplies. The long-term cost, however, is devastating. Without education, children are locked out of stable employment and remain trapped in the very cycle visitors hope to help them escape.

Child selling is also closely tied to exploitation. Many children do not keep the money they earn. A portion often goes to adults or covers the cost of the goods they are selling. For the long hours they work, the benefit to the child is minimal, while the risks are considerable.

The Hidden Dangers Children Face

Children on the streets are vulnerable in ways travellers rarely see. Long evenings without supervision expose them to sexual exploitation and trafficking. Sapa, in particular, has become a known target for predators due to the visible presence of children at night. Girls and young teenagers from border regions are also at risk of being trafficked to China. This is not speculation; it is a documented reality.

Older children, particularly girls aged thirteen to sixteen offering cheap trekking services, are also deeply vulnerable. Many live away from home, separated from family and community support. Trekking with a child may feel kind, but it increases their exposure to danger and is illegal for good reason. There is no shortage of skilled, knowledgeable adult guides who can offer a far safer and richer experience.

Why Buying from Adults Makes a Difference

Supporting adult artisans and guides is not only ethical, it is transformative. Many Hmong and Dao women earn supplementary income through guiding, alongside their roles as farmers and mothers. With only one rice harvest per year, most families cannot grow enough food to sell and must purchase essentials. Income from guiding or handicrafts helps bridge this gap.

Their textiles are not souvenirs made for tourists alone. They are intricate, symbolic works created using traditional dyes, batik techniques, embroidery, and brocade weaving passed down through generations. Buying these items out of genuine interest, rather than guilt, honours the skill and cultural knowledge behind them.

Trekking with licensed local guides offers something equally meaningful. Adult guides bring lived knowledge of the land, history, and spiritual traditions of their communities. Many travellers describe these experiences as deeply personal and life-changing.

Tourism, Responsibility and the Bigger Picture

The Ha Giang Loop offers a clear example of how tourism choices matter. When travellers ride with Vietnamese-owned agencies, guided by non-local staff and staying in Vietnamese-owned accommodation, ethnic minority villages bear the disruption without seeing the benefits. Cameras point inward, but income flows outward.

A more regenerative model supports guides and hosts born into these communities, ensuring tourism contributes to local resilience rather than extraction.

You may notice signs in Sapa discouraging visitors from trekking with Hmong and Dao women. From our perspective, meaningful employment for parents is the only real solution to child selling. Many adults over thirty are illiterate due to historical exclusion from education, which limits access to town-based employment. Yet their willingness to work is evident. Men wait daily for manual labour. Women guide when opportunities arise. Tourism, when done thoughtfully, can meet people where they are.

Choosing Ethical Travel

When you choose not to buy from children, you are not withholding kindness. You are choosing long-term safety, education, and dignity over short-term comfort. When you support adult guides, artists, and hosts, you help create livelihoods that keep families together and children in school.

At ETHOS, we believe travel should be immersive, respectful and regenerative. We invite you to walk with care, listen deeply, and make choices that honour the people who welcome you into their mountains and homes.

Experience This With ETHOS

Join our ethical trekking tours in Sapa

Stay in authentic Hmong homestays

Discover Sapa’s culture with our workshops

The Serene Power of Northern Vietnam’s Man Made Hydro Lakes

Northern Vietnam’s hydro lakes blend human vision with natural beauty. These vast waters support local life, clean energy and quiet travel far from the crowds.

Northern Vietnam is known for its dramatic mountains, lush forests and winding rivers, but it is also home to some of Southeast Asia’s most impressive hydro lakes. These vast bodies of water are the result of major engineering projects, yet they look entirely at home within the landscape. Their sheer scale and calm beauty make them destinations that feel both awe inspiring and deeply peaceful.

A Landscape Transformed by Vision and Engineering

The region’s hydro lakes were created through large scale dam projects that harness the power of fast flowing mountain rivers. When the valleys were flooded, the geography changed forever. What once were river channels and terraced slopes became expansive lakes that stretch for kilometres, curving and branching like inland fjords.

Although these lakes are artificial, they do not feel industrial. The mountains remain untouched and thick with vegetation. Clouds drift low across the water, and the air carries a fresh, earthy scent. The result is a landscape shaped by humans but fully embraced by nature.

Endless Horizons of Still Water and Mist

Visitors are often struck by the way the lakes reflect the surrounding scenery. On a quiet morning the water can appear perfectly still, like polished glass. Forested ridges, limestone cliffs and tiny floating houses are mirrored with astonishing clarity. The atmosphere is often enhanced by gentle mist that rolls across the surface, giving the entire scene a dreamlike quality.

In some areas small islands rise from the water, covered with bamboo and wild plants. These islands create beautiful compositions that feel almost cinematic. In the late afternoon when the sun sinks behind the hills, the lakes glow with soft light that feels peaceful and ancient.

Local Life Along the Water

Despite their remote appearance, the hydro lakes are living landscapes. Local communities fish, farm and travel across the water daily. Long wooden boats glide between floating homes, fish farms and forested peninsulas. Markets gather along the shores and visitors can often share meals of freshly caught fish cooked with fragrant herbs.

Tourism here remains understated. Instead of busy resorts, travellers can find homestays, small eco lodges and guided boat trips that encourage quiet appreciation rather than fast paced sightseeing.

Power, Progress and Preservation

These hydro lakes are vital for Vietnam’s energy supply. They produce electricity for millions while reducing reliance on fossil fuels. Yet what stands out is how gracefully the environment has adapted. Wildlife remains abundant, forests stay green and the lakes have become a source of both sustainability and scenic value.

They show that development does not always have to diminish natural beauty. With careful planning and respect for the land, it can even create new spaces for reflection, adventure and cultural life.

A Destination Worth Exploring

Northern Vietnam’s hydro lakes are functional reservoirs and places where nature and human design exist in harmony. Whether you explore by boat, hike the surrounding hills or simply sit at the shoreline, the stillness and scale will leave a lasting impression.

If you are drawn to landscapes that feel wild yet welcoming, this is a journey worth taking. It is not only about seeing something extraordinary. It is about feeling connected to a place where power and peace flow together.

Ready to Explore on Two Wheels

For those seeking a deeper connection with these waterways, remote mountain communities and the hidden paths in between, our guided motorbike adventures offer a truly immersive way to travel. We ride through highland passes, along lake shores, into caves and across cultural landscapes that many visitors never reach. If you want to combine the freedom of the open road with meaningful, slow travel, explore our routes:

Ride Caves and Waterways

https://www.ethosspirit.com/ride-caves-waterways-5-days

Ride the Great North

https://www.ethosspirit.com/ride-the-great-north

Join us, breathe the mountain air and experience the spirit of Vietnam with every mile.

Tet in Northern Vietnam: What to Expect, When to Travel, and How to Prepare

Tet shapes travel, family life, and village celebrations across northern Vietnam. From red envelopes and homecomings to crowded roads and post-Tet festivals, here is how to plan a thoughtful journey around Tet 2026.

Each year, as winter softens its hold on the Hoàng Liên mountains and the first plum blossoms open along stone walls and village paths, Vietnam moves into its most meaningful season. Tết Nguyên Đán, the Lunar New Year, marks a time of renewal, homecoming, and intention.

In the northern highlands of Sapa, Ha Giang, and the wider border regions, Tet shapes the rhythm of daily life, travel, and community celebration. For visitors, understanding this period allows journeys to unfold with greater care, respect, and connection.

When Is Tet in 2026?

In 2026, Tet begins on Tuesday 17th February, marking the start of the Lunar New Year.

Although the official holiday lasts several days, preparations begin weeks in advance and the effects continue well beyond the celebration itself. Travel patterns, accommodation availability, and village life are influenced for up to three weeks around Tet.

What Is Tet and How Is It Celebrated?

Tet marks the beginning of the lunar calendar and a turning point in family, agricultural, and spiritual life. Across Vietnam, people return to their ancestral homes, clean and repair houses, and prepare food that carries memory, care, and meaning.

Altars are refreshed with kumquat trees, peach blossom branches, incense, and offerings. Kitchens fill with the slow scent of simmering broths and sticky rice wrapped in banana leaves. The first days of the new year are spent visiting relatives, offering good wishes, and resting after a year of work.

One of the most visible customs during Tet is the giving of lì xì, red envelopes containing small amounts of money. These are given primarily to children, but also to elders and unmarried adults, as a symbol of good fortune, health, and prosperity for the year ahead. The red envelope itself carries meaning, representing luck and protection, rather than the monetary value inside. For children, receiving lì xì is a moment of excitement and joy, often accompanied by blessings for growth, strength, and happiness.

In the mountains, Tet aligns with a pause between farming cycles. Fields rest, tools are set aside, and time is made for family gatherings, storytelling, and preparation for the celebrations that follow.

What Tet Means for Travel in Vietnam

Travelling during Tet requires thoughtful planning and realistic expectations.

In the days leading up to and following the New Year, transport networks become extremely busy as families return home. Buses, trains, and flights often sell out far in advance. Many small, family-run businesses close for several days so that owners and staff can spend time with their families.

For travellers, preparation makes a significant difference. Booking accommodation early, allowing extra time for journeys, and accepting a slower pace can turn disruption into an opportunity to witness daily life at a meaningful moment in the year.

The Ha Giang Loop After Tet

The Ha Giang Loop is one of northern Vietnam’s most iconic journeys, and Tet brings a sharp rise in visitor numbers.

From around two days after Tet, the Loop becomes extremely busy. Homestays and hotels fill quickly and often reach full capacity. Roads see heavy traffic from tour groups, motorbikes, and domestic travellers returning from holiday.

For approximately ten days after Tet, riding conditions can feel congested, and accommodation options are limited. Those planning to travel during this period should book well in advance. Travellers seeking quieter roads and a more spacious experience may prefer to arrive before Tet or wait until later in the season.

Sapa During and After Tet

Sapa follows a similar rhythm.

From the second day after Tet, the town and surrounding valleys experience a significant increase in visitors. Hotels fill, trekking routes become busier, and transport costs may rise.

This period of heightened activity usually lasts around ten days, after which the region gradually returns to a calmer pace. Travellers hoping for quieter trails and deeper village engagement may wish to plan their visit outside this window.

Village Festivals After Tet in Hmong and Dao Communities

After the main Tet celebrations each spring, villages around Sapa begin to host their own cultural festivals. These gatherings are deeply rooted in local tradition and follow village-specific calendars rather than national schedules.

Festivals typically begin early in the morning and continue through the day. Larger villages host especially lively celebrations, drawing neighbouring communities together. Events include a wide range of cultural activities and folk games that emphasise health, strength, and skill. Physical ability is highly valued, as agriculture remains central to daily life in the highlands.

Music, dancing, shared meals, and rice wine are all part of the day. Perhaps the most anticipated moment comes with the unveiling of newly handmade traditional clothing. Months of winter are spent preparing these garments, using indigo-dyed organic hemp and intricate silk embroidery. Each piece reflects patience, identity, and pride in craftsmanship passed down through generations.

Alongside these traditional garments, some young women choose modern fabrics and bolder styles, often affectionately referred to as the “glitter girls”. Their presence adds humour, creativity, and a living sense of fashion to the celebrations.

Hmong New Year festivals mark the end of the harvest and the beginning of a new year in the Hmong calendar. They are a time for honouring ancestors, strengthening community bonds, exchanging small gifts, and reflecting on the year that has passed while setting intentions for the one ahead.

For visitors, these festivals offer a rare opportunity to witness culture as it is lived, not staged. Respectful behaviour, local guidance, and patience are essential, as these gatherings remain first and foremost for the communities themselves.

Planning Your Journey Around Tet

Tet can be a rewarding time to travel in northern Vietnam when approached with awareness and care.

Accommodation should be booked early, particularly in Ha Giang and Sapa. Flexible itineraries allow room for transport delays and business closures. Travellers who align their journeys with local rhythms often find deeper connection than those moving too quickly.

At ETHOS, our experiences are shaped in close collaboration with Hmong and Dao partners, following the seasonal cycles of land and village life. Some travellers arrive before Tet to experience quiet mountain days. Others choose to come later, when village festivals bring colour, movement, and shared celebration back to the valleys.

Listening to the people who live here remains the foundation of meaningful travel, whatever the season.

Sapa Beyond the Town: Discovering the Real Heart of the Mountains

Sapa is far more than a busy mountain town. Travel beyond the tourist trail to discover remote villages, deep forests and a rich living culture.

Sapa Is Bigger Than You Think

Contrary to what many people believe, Sapa is not a single village or a quiet valley. It is a vast geographical district that stretches across mountains, forests and river valleys. Driving from one end to the other takes around four hours.

Within this large area lies the Hoang Lien Son National Park and more than 90 villages and hamlets. Many of these places rarely see visitors at all, remaining deeply connected to traditional ways of life and the natural environment.

Sapa Town and the Tourist Villages

Like many destinations in Vietnam, Sapa has a central hub. Sapa town is where most travellers arrive, stay and use as a base. It is lively, crowded and full of hotels, cafes and tour offices.

The villages closest to the town include Cat Cat, Lao Chai, Ta Van and Ta Phin. Because they are easy to reach, they attract the highest number of visitors. These villages often have a backpacker atmosphere and are the places people usually refer to when they talk about Sapa being touristy. While they can be enjoyable, they are not the best places to experience the region’s deepest culture or most dramatic landscapes.

Why Going Further Makes All the Difference

To truly experience Sapa, it is essential to explore beyond the main routes. Once you do, it quickly becomes clear why this region is so special.

Remote villages offer quieter trails, wider views and genuine daily life. The pace slows down. The mountains feel bigger. The connection to the land becomes stronger. This is where Sapa reveals its true character.

Experiences That Show the Real Sapa

Sapa offers far more than classic trekking, although guided walks and homestays are unmissable. The region is also ideal for textile workshops, forest walks and local food experiences. You can join market visits, go foraging, take photography courses or enjoy wild swimming in hidden spots.

For those who enjoy adventure, single or multi day motorbike journeys, mountain summits and camping trips open up vast and beautiful areas. In summer, the cooler mountain air provides a welcome escape from the heat found elsewhere in Vietnam.

A Place to Learn, Connect and Slow Down

Sapa is a place to immerse yourself, not just to visit. It invites you to learn from people who live close to the land and to reconnect with nature in a meaningful way. When explored thoughtfully, it becomes one of the most rewarding highlights of any journey through Vietnam.

Experience This With ETHOS

Join our ethical trekking tours in Sapa

Stay in authentic Hmong homestays

Discover Sapa’s culture with our workshops

Cherry Blossom Season in Sapa: When the Highlands Turn Pink

Each December, Sapa’s cold highlands briefly turn soft pink as wild cherry blossoms bloom across the tea hills. It is a quiet, beautiful winter moment not many travellers expect.

A Winter Transformation in the Sapa Highlands

There is something very special about cherry blossom season in Sapa. Each year in December, for around fifteen days, the highlands change completely. Cold air settles over the mountains, winter winds sweep across the valleys, and suddenly the landscape glows with soft shades of pink.

Against the grey skies and misty hills, the blossoms feel even more striking. The contrast between winter’s chill and the gentle flowers makes this season short, calm and deeply memorable.

A Landscape Painted in Pink

During this brief period, hillsides that are usually green or quiet become lively with colour. Walking through Sapa at this time feels like stepping into a different world, where nature slows down and invites you to stop and look more closely.

Wild Himalayan Cherry Blossoms Explained

The blossoms seen in Sapa are wild Himalayan cherry trees, known scientifically as Prunus cerasoides. They are sometimes called sour cherry and are native to Southeast Asia.

Where These Trees Grow

These cherry trees grow only in temperate climates at elevations above 1,200 metres. Their natural range stretches from the Himalayas through to northern Vietnam, making Sapa an ideal home for them.

Planted along tea hills, the trees bloom just once a year, which is why the season feels so precious and fleeting.

The Best Place to See Cherry Blossoms in Sapa

O Long Tea Hill and O Quy Ho

The best place to see cherry blossoms in full bloom is O Long Tea Hill in the O Quy Ho area, about 8 km from Sapa Town. Here, rows of tea plants sit beneath flowering cherry trees, creating a peaceful and unforgettable scene.

Early mornings are especially beautiful, when mist drifts through the hills and pink petals glow softly in the cold winter light.

Ethical Trekking in Sapa: Travel with Purpose

Travel responsibly in Sapa with ETHOS. Our ethical treks support local guides, protect the environment, and create meaningful connections between travellers and communities.

A Meaningful Way to Explore the Mountains

Trekking with an ETHOS guide in Sapa provides more than just a scenic adventure. It offers a valuable source of income for local communities, ensures fair wages, and fosters cultural respect. Our team of Hmong and Dao guides create authentic connections rather than staged performances. Every step you take supports families who share their land, culture, and stories with honesty and pride.

How Ethical Tourism Supports Communities

When travellers choose locally led experiences, the benefits reach entire villages. Homestays, markets, and artisan workshops thrive through responsible tourism. At ETHOS, we reinvest directly into education, healthcare, and cultural preservation initiatives. This approach allows tourism to become a positive force for long-term development rather than short-term gain.

The Cost of Mass Tourism

Large tour companies often exploit communities by taking most of the profits while underpaying guides and damaging the environment. Cultural traditions risk being reduced to performances for visitors, leaving locals with little benefit or pride. These practices erode the authenticity that makes Sapa so special.

Travelling Consciously in Sapa

There is a better way. Conscientious travellers can make a real difference by choosing ethical options. Many parts of Sapa are perfect for responsible tourism. The region’s ethnic diversity, stunning mountain scenery, and strong community spirit make it ideal for sustainable travel. Small-scale tourism ensures that locals, not corporations, receive the rewards of visitors’ journeys.

ETHOS – Spirit of the Community

ETHOS is built on collaboration and respect. Every experience we offer is designed together with local people, ensuring that both travellers and hosts benefit. Our model focuses on women-led tourism, giving female guides opportunities for financial independence and professional growth.

We pay our guides fairly and directly, avoiding the middlemen who often take most of the earnings. Cultural immersion lies at the heart of every experience, from shared home-cooked meals to stories told beside the fire.

What Makes ETHOS Different

Travellers and international media recommend ETHOS because of our deep, genuine relationships with the local community. We keep group sizes small, personalise each trek, and adapt every experience to the needs and interests of our guests.

By avoiding mass tourism practices, we protect Sapa’s landscapes and traditions. Visitors can see exactly how their contribution supports local families, schools, and cultural heritage. This creates a journey that is both meaningful and sustainable.

A Shared Future

Ethical tourism protects landscapes, preserves traditions, and strengthens communities. Every responsible choice contributes to a better experience for travellers and a sustainable future for locals.

We believe that with care and thought, every traveller can become part of the solution rather than the problem. Together, we can ensure that the beauty of Sapa continues to thrive for generations to come.

Closing Thought

Travel with purpose. Walk with respect. Leave a positive trace on the land and in the hearts of those you meet.

Riding the Backroads of Dien Bien Phu

Join us on a four-day motorbike journey through the quiet valleys and hidden trails of Dien Bien Phu. Along the way, we shared meals, stories and moments of connection with the land and its people.

A Journey Beyond the Beaten Path

Over four days we travelled by motorbike through the upland plateaus and quiet valleys west of Sapa. The route led us ast calm lakes, terraced hillsides and small farming communities where life follows the rhythm of the seasons. It was a journey into the heart of the mountains, where every bend in the road revealed something new and beautiful.

Learning from the Land

Our local hosts guided us with warmth and patience, stopping often to walk, share food and talk about the land. They showed us how to forage for wild herbs, edible shoots and mountain mushrooms. Each stop uncovered another layer of local knowledge, passed down through generations and shaped by a deep relationship with the forest and fields.

Evenings by the Fire

When the day’s riding was done, we gathered beside small fires to share bowls of rice and stories. Conversations flowed in a gentle mix of Hmong, Vietnamese and English. The nights were filled with laughter, soft music and the quiet comfort of companionship under a sky full of stars.

Through the Backroads of Dien Bien Phu

These photographs capture the beginning of that journey through the backroads of Dien Bien Phu. Each image tells a part of the story — of movement, discovery and connection with a landscape that holds both history and peace.

Last Chance to See: A Century of Hmong Clothing in Northern Vietnam

A visual journey through Hmong clothing across four regions of Northern Vietnam, revealing how tradition, identity, and textile art have survived for over a century.

Last Chance to See: Clothing, Change, and Continuity

As part of a photo series titled Last Chance to See, ETHOS explores how clothing has changed over more than a century while still holding deep cultural meaning. This series looks closely at what has endured, what has adapted, and why traditional dress continues to matter today.

Today’s focus is on the Hmong people living in four distinct regions of Northern Vietnam: Mu Cang Chai, Sapa, Ha Giang, and Bac Ha. Each region tells its own story through colour, texture, and design.

The Hmong People and Cultural Identity

Throughout recorded history, the Hmong have remained identifiable as Hmong. This continuity comes from maintaining their language, customs, and ways of life, even while adopting elements from the countries in which they live.

Clothing plays a central role in this identity. It is not simply something to wear, but a visible expression of belonging, heritage, and pride.

Regional Differences in Hmong Dress

Many Hmong groups are distinguished by the colour and details of their clothing. Black Hmong traditionally wear deep indigo dyed hemp garments, including a jacket with embroidered sleeves, a sash, an apron, and leg wraps. Their clothing is practical, durable, and rich in subtle detail.

Flower Hmong are known for their brightly coloured traditional costumes. These outfits feature intricate embroidery, bold patterns, and decorative beaded fringe, making them immediately recognisable.

Paj Ntaub: The Language of Cloth

An essential element of Hmong clothing and culture is paj ntaub, pronounced pun dow. This is a complex form of traditional textile art created through stitching, reverse stitching, and reverse appliqué.

Meaning, Skill, and Tradition

Traditionally, paj ntaub designs are ornamental and geometric. They are mostly non representational and do not depict real world objects, with the occasional exception of flower like forms. The making of paj ntaub is done almost exclusively by women.

These textiles are sewn onto clothing and act as a portable expression of cultural wealth and identity. Paj ntaub play an important role in funerary garments, where the designs are believed to offer spiritual protection and guide the deceased towards their ancestors in the afterlife. They are also central to Hmong New Year celebrations.

Before each New Year, women and girls create new paj ntaub and new clothing. Wearing clothes from the previous year is considered bad luck. These new garments reflect creativity, skill, and even a woman’s suitability as a successful wife.

Why Hmong Clothing Endures

Despite major cultural and social change over the past century, Hmong clothing has endured. Its survival lies in its deep connection to identity, belief, skill, and community. Each stitch carries meaning, and each garment tells a story that continues to be passed from one generation to the next.

Top 10 Offbeat Things to Do in Sapa (Sustainable Adventures You’ll Never Forget)

Explore the most unique and sustainable things to do in Sapa, from guided foraging treks and artisan workshops to hidden waterfalls and remote village adventures.

Discover Sapa Beyond the Usual Trek

Sapa is world-famous for its misty mountains, terraced rice fields, and vibrant ethnic diversity. Yet beyond the well-trod paths lies a deeper, more soulful side of northern Vietnam — one of community, culture, and connection with nature.

At ETHOS – Spirit of the Community, we believe travel should leave a positive footprint. Every experience we offer is designed around cultural integrity, environmental care, and genuine human connection.

Here are our Top 10 Offbeat Things to Do in Sapa — experiences that bring you closer to the people, stories, and landscapes that make this place extraordinary.

1. Camp & Forage with a Hmong Guide

Sustainable trekking Sapa

Venture into the mountains with a local Hmong guide and learn to identify wild herbs, edible plants, and forest fungi. Spend a night under the stars, cook over a campfire, and listen to traditional stories about the land.

👉 Join the Foraging & Camping Trek

2. Stay with a Dao Family in a Mountain Homestay

Best homestays Sapa

Immerse yourself in Dao culture during a family homestay surrounded by rice terraces. Learn about herbal medicine, help prepare meals, and enjoy mountain tea by the fire. This experience supports rural women and preserves traditional wisdom.

👉 Book an Ethical Homestay Experience

3. Canyoning in Hoàng Liên Sơn National Park

For adrenaline lovers, descend waterfalls and navigate natural pools in Vietnam’s most spectacular mountain range. Led by trained local guides, this eco-adventure combines safety, sustainability, and excitement.

👉 Explore Canyoning Adventures

4. Take a Motorbike Loop to Tay Villages

Ride west through lush valleys and bamboo forests to visit Tay communities. Stop for lunch in a local home and learn about their stilt-house architecture and weaving traditions. This scenic route showcases rural life beyond Sapa town.

👉 Discover Sapa by Motorbike

5. Trek to Hidden Waterfalls on the Woodland Way

ETHOS’s signature Woodland Way Trek takes you deep into ancient forests, past quiet farms and secret waterfalls untouched by mass tourism. Ideal for photographers and nature enthusiasts.

👉 Trek the Woodland Way

6. Learn Batik in a Hmong Artisan Workshop

Cultural workshops Sapa

Join a Hmong artisan to learn the ancient craft of indigo batik. Create your own hand-dyed cloth using beeswax and natural pigments. Each workshop supports local women artisans.

👉 Book a Batik Workshop

7. Summit the Magnificent Ngu Chi Son Mountain

Known as the “Five Fingers of the Sky,” Ngu Chi Son offers one of Vietnam’s most rewarding climbs. ETHOS guides lead small, responsible expeditions to the summit — balancing adventure with ecological respect.

👉 Climb Ngu Chi Son

8. Visit Sapa’s Hidden Lakes

Beyond the famous Love Waterfall lies a network of serene mountain lakes where locals fish and gather medicinal plants. ETHOS guides will take you to quiet, reflective spots rarely visited by outsiders.

👉 Discover Sapa’s Secret Lakes

9. Wander Through Ancient Forests on our Twin Waterfalls Walk

Experience Sapa’s biodiversity on guided walks through The Hoang Lien Son National Park forests. Learn about indigenous plant use, local conservation efforts, and reforestation projects ETHOS supports.

👉 Join a Forest Trek

10. Explore Tea Plantations & Wild Himalayan Cherry Fields

Ride or walk through Sapa’s highland tea gardens and wild cherry groves. Visit family-run farms producing organic tea, and sip with a view over cloud-wrapped valleys.

👉 Visit the Tea Trails of Sapa

Travel with Purpose

Every ETHOS adventure supports community empowerment, environmental protection, and cultural preservation. By travelling with ETHOS, you directly help local families and contribute to a more sustainable future for Sapa.

Ready to explore responsibly?

👉 View All ETHOS Experiences

Why We Built ETHOS in Sapa: For Community, Culture and Connection

Learn why ETHOS was created in Sapa and how community based tourism supports local guides, families and cultures through fair work, shared stories and meaningful connection.

1. Understanding the Context

When you travel into the highlands around Sapa, you enter a world of steep valleys, rice-terraced slopes, hillside farmers, and the daily rhythms of ethnic minority communities such as the Hmong and Dao. Yet alongside that beauty lie complex realities. Many of the communities here have long been marginalised socially, economically and culturally.

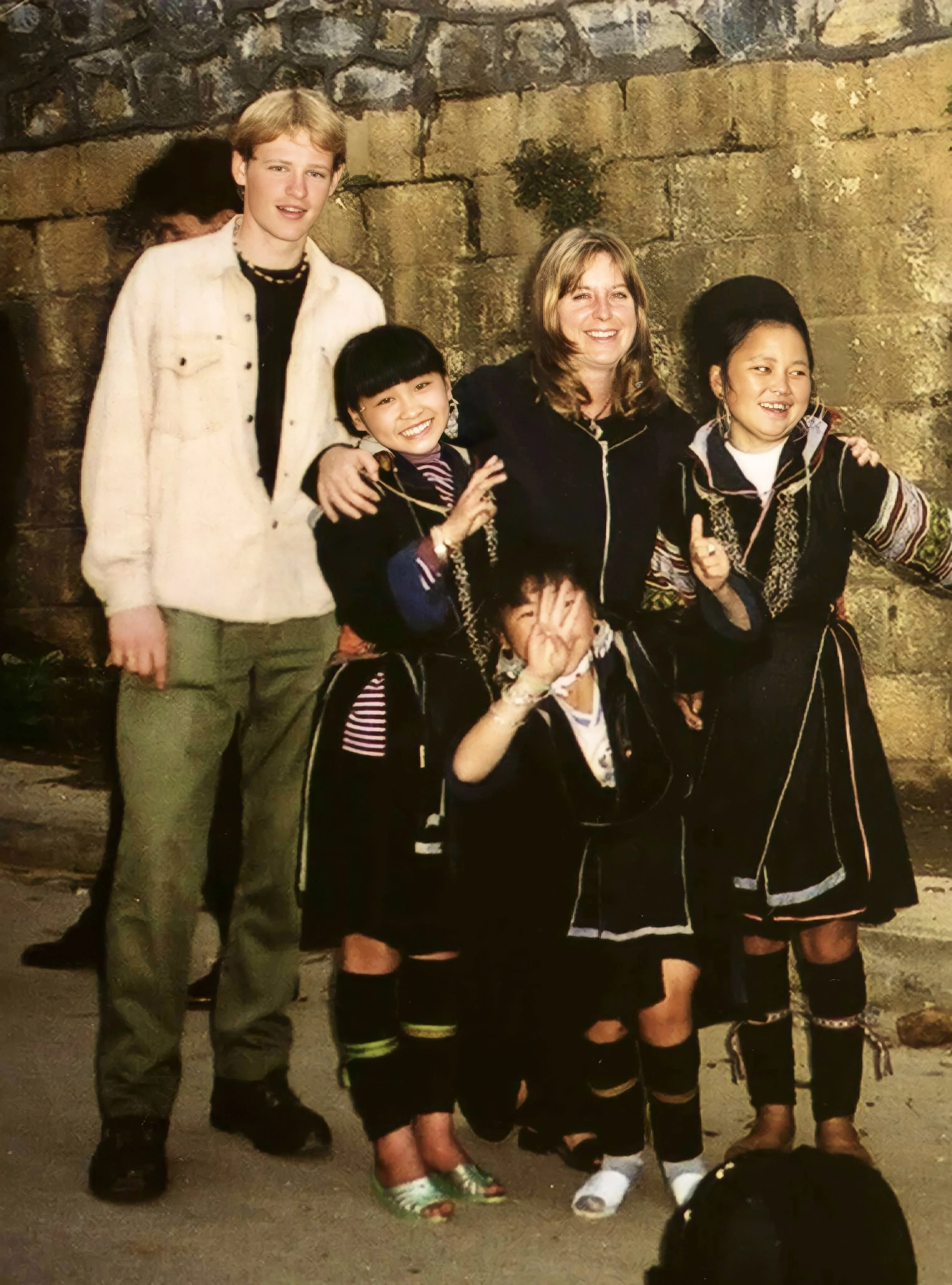

During his early work here, the company’s founding partner, Phil Hoolihan, describes meeting young Hmong girls who, barefoot and curious, appeared at a camp in the mountains asking to practise English. Their hunger for more than the limited opportunities they saw planted the seed of what ETHOS would eventually become.

In that moment, one realisation took hold: tourism need not be a one-way street. Instead of simply entering a landscape, we could enter a conversation. Instead of only visiting homes, we could build relationships. Instead of extracting experiences, we could help sustain livelihoods, heritage and hope.

2. What Led Us to Act

Phil, together with his partner Hoa Thanh Mai, recognised that many conventional tourist operations in the region follow predictable routes and visitor numbers, yet seldom invest in the people, language, culture or environment of the area.

In their reflections, they asked: could we create something different? A venture that is locally rooted, values-led, and community-first, not just profitable? As Phil writes: “We didn’t want to build another tour company or a feel-good charity. We wanted to create something rooted, regenerative and real.”

By 2012, the decision was made. They moved back to Sapa, started small, with only a few guides, two basic trek options, one laptop and a shared desk. That humble beginning marked the birth of ETHOS: Spirit of the Community.

3. Our Mission and Model

From the outset, our guiding principle has been that travel can uplift, connect and sustain. We believe that every journey should be more than a photograph. It should be relationship-building, culture-sharing, and landscape-respecting.

We operate with four interlinked priorities:

Fair employment and empowerment of guides: Our guides are local women and men from the villages, and they lead the experiences. Their intimate knowledge, language and heritage bring authenticity.

Support for local families, craftswomen and farmers: Whether it is staying overnight in a village homestay, sharing a home-cooked meal, or taking a textile workshop with a skilled artisan, the idea is to work with rather than on the community.

Reinvestment into community development: A portion of every booking supports education for ethnic minority youth, health and hygiene programmes, conservation work and our community centre in Sapa.

Slow, respectful, off-the-beaten-track travel: We do not offer large group tours or queue at the viewpoints. Instead, we walk through rice terraces, stay in farmhouses, join in batik or embroidery workshops, and ride quiet roads by motorbike. It is about time, immersion and connection.

4. How the People Tell the Story

To understand why ETHOS exists, it helps to hear from those whose lives are intertwined with its creation.

Phil Hoolihan recalls the camp by the ridgeline where Hmong girls sat listening, learning English and dreaming. That moment triggered the question: what if tourism could lift culture rather than erode it?

Hoa Thanh Mai grew up in an agricultural town near Hanoi, the daughter of a ceramics-factory worker and a mother involved in textile trading. She studied tourism because she believed travel could be a tool of connection, not merely business.

Ly Thi Cha, a Hmong youth leader and videographer with ETHOS, embodies the spirit of bridge-building: interpreter, guide, cultural storyteller. Her presence shows the model in practice: local leadership, local voice, local vision.

Through their journeys, you can see how ETHOS is not an addition to community life but an extension of it. The guides are voices, the homes are real, the musk of smoke from the hearth, the murmur of family conversations, the weight of a needle in the hand of a craftswoman.

5. Why It Matters

You might ask: why is this so important? Because, when done thoughtfully, community-based tourism can be transformational.

It shifts power: from a few tour operators deciding where to lead visitors, to communities co-creating what they show and how they show it.

It safeguards culture: traditional crafts, stories and landscapes become living and evolving, not museum pieces or commodified clichés.

It generates dignity: when local guides share their own lives, and when income goes directly to extended families, the ripple effect strengthens livelihoods.

It deepens travel: for you, the traveller, this is not about ticking boxes; it is about altering perspective, slowing down, listening and noticing. “The most memorable journeys are not always the most comfortable or convenient,” as our website puts it.

It anchors sustainability: by linking tourism to education, healthcare and the environment, travel becomes support rather than strain.

6. How You Can Walk With Us

If you decide to join our journey, here is what you will experience:

Trekking through hidden ridges, paddies and hamlets with a local guide who has grown up here.

Homestays in village homes: food cooked over the fire, slow evenings, stories shared in the morning mist.

Textile or herb-foraging workshops led by craftswomen and keepers of herbal knowledge, not by outsiders.

Motorbike loops that avoid tourist hotspots and instead meander through remote valleys, tea plantations and lesser-seen paths.

A guiding ethos: come with curiosity, leave with muddy boots, full hearts, and friendships that linger.

7. In Summary

We built ETHOS in Sapa because the mountains here hold scenery, culture, craft, community and heritage that deserve partnership, not performance. We chose to centre women guides, local artisans, storytellers and farmers. We chose small groups, slow rhythms and mindful travel. We chose to measure success not just in tours sold but in lives enriched, traditions honoured and landscapes respected.

If you travel with ETHOS, you are choosing more than a route through rice terraces. You are choosing a journey that shifts the focus of tourism from convenience to connection, of visitor from spectator to participant, of region from “destination to consume” to “community to share with”.

Welcome. We are glad you are here, and we look forward to walking the path together.

Experience This With ETHOS

Join our ethical trekking tours in Sapa

Stay in authentic Hmong homestays

Discover Sapa’s culture with our workshops

Snow in Sapa. Truth, myth and the quiet magic of a rare winter

A rare snowfall in Sapa transforms the highland landscape and reveals a quieter side of the mountains. In this honest guide we explore the difference between frost and true snow, share verified historical snowfall records from 1990 to the present day and explain why these fleeting winter moments hold such meaning for the communities who live here.

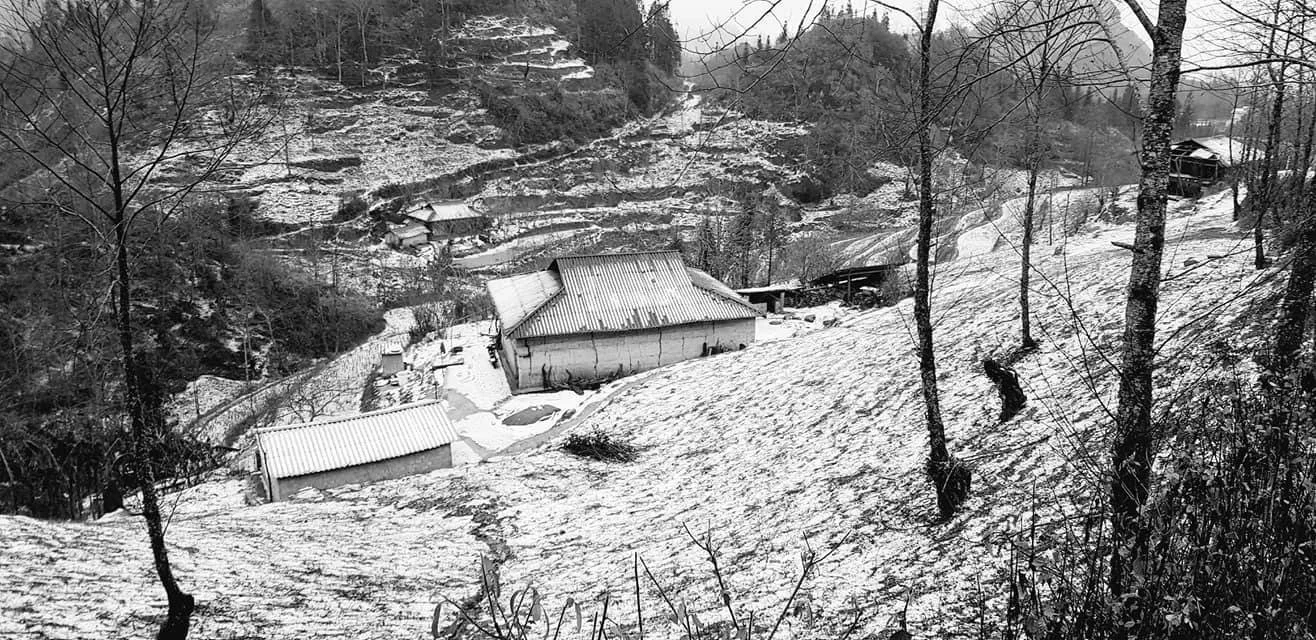

Winter in the Highlands. Mist, Frost and Quiet Days

Winter in the northern mountains of Vietnam arrives gently. It drifts into the terraced valleys on slow banks of mist, settles in the hollows of bamboo forests and chills the ridge lines of the Hoang Lien range with a sharp, crystalline breath. At this time of year, life for Hmong, Dao and Tay families becomes more reflective. Fires burn low in earthen hearths, animals are sheltered, and preparations begin for the new agricultural cycle that follows the Lunar New Year.

In this subdued season the highlands reveal a quieter beauty. Frost rims the grasses at daybreak and thin ice patterns appear on still water. Yet none of these common winter signs can prepare you for the rare and gentle arrival of real snow.

Sorting truth from trend. Snow, frost and the digital mirage

Over the last decade, social media has woven a complicated tale around Sapa and the prospect of a winter snowfall. Photographs of icy railings on Fansipan or frozen bamboo at O Quy Ho Pass are often shared under bold claims that the town itself has been blanketed in white. Visitors arrive with high hopes, sometimes shaped more by digital imagery than by the lived realities of the local climate.

These icy scenes have their own beauty, but they are usually frost or rime. Frost forms when moisture freezes onto cold surfaces. It can create a sparkling, sculptural landscape that feels almost otherworldly, especially on Fansipan where temperatures regularly dip below freezing. These frost events occur several times every winter above about 2,800 metres and they are a natural part of life on the mountain.

Snow is different. Snowflakes form in the cloud itself. They fall, gathering on rooftops, footpaths and terraces. Snow transforms the world with softness rather than sharpness. It also happens infrequently in Sapa town, which is why many frost events are mistakenly promoted as snowfall. At ETHOS we believe that honesty honours both the mountains and the people who call them home. When snow truly arrives, it deserves to be understood in the context of how rare and precious it is.

Genuine snow in Sapa town. Four real events since 1990

Once we strip away frost events, sleet, cold mist and the noise of tourism marketing, the list becomes far more modest. Only four snowfalls have been verified in Sapa town since 1990. These are supported by the Vietnam National Centre for Hydro-Meteorological Forecasting, by climate logs and by the memories of families who live and farm here.

What follows is a clear record of those events, along with detail on how long the snow fell and how long it lasted.

1. March 16, 2011. A brief and gentle snowfall at around 1,600 metres

This was a short, late-season event that surprised many residents. Snow fell for about an hour in the late morning and lightly dusted the roofs and shaded corners of Sapa town. With the sun still strong in mid March, the snow melted entirely before the afternoon had passed. Although delicate and short lived, this was a genuine snowfall, confirmed by official observers.

2. December 15, 2013. A moderate and memorable night of snow

On this cold winter night, snow formed in the early hours and continued until sunrise. Between three and five centimetres settled across the town centre, while the road towards Thac Bac at around 1,900 metres received seven to ten centimetres. Children woke to a world softened by white. Most of the snow faded away by early afternoon, although hollows and forest edges held onto their pale covering for a little longer. This was the longest lasting town snowfall since 1990.

3. February 19, 2014. A short lived but authentic winter moment

This was another verified snowfall, although very light. Between half a centimetre and one centimetre gathered on cars and rooftops before melting almost immediately. The snow fell for less than forty minutes. It is sometimes confused with the frost and residual ice that appeared on nearby passes that same week, but the snowfall in town was real, if fleeting.

4. January 24 to 25, 2016. The largest modern snowfall in Sapa town