History of Sapa

History of Sapa, Vietnam: Ethnic Traditions, French Legacy & Modern Tourism

History of Sa Pa

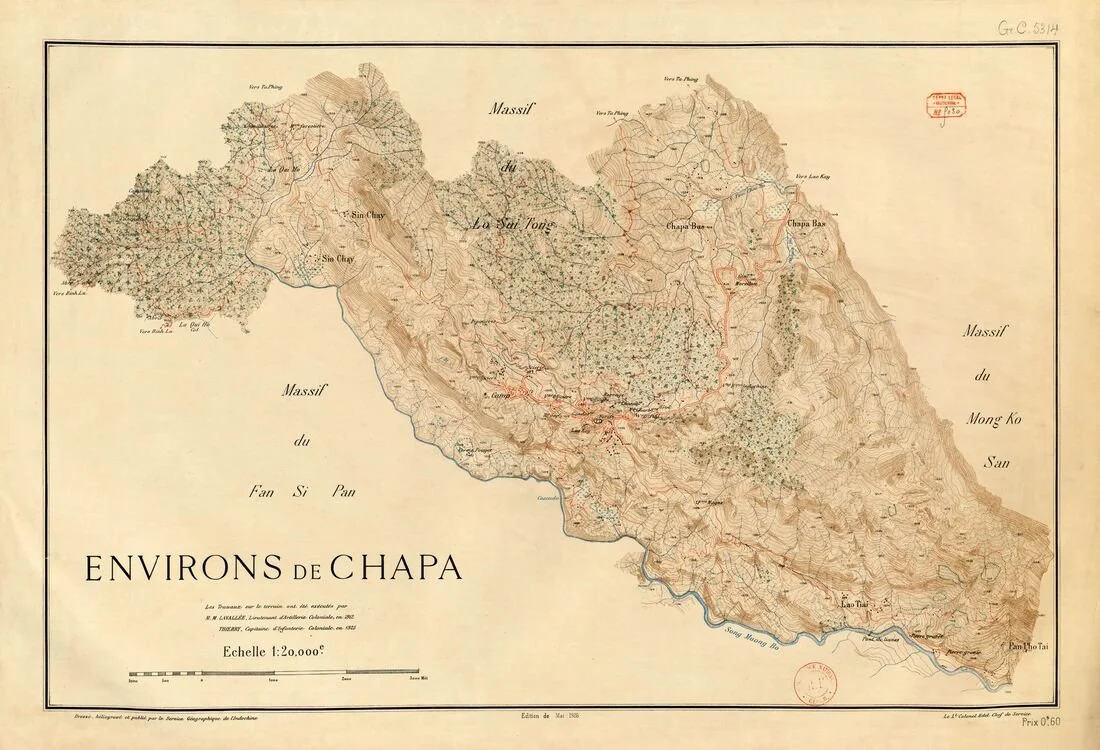

In the late nineteenth century, the French colonial authorities in northern Vietnam (then Tonkin) began the first formal surveys of the region’s ethnic minorities. The earliest scientific expeditions reached Lào Cai Province in 1898 and, by 1903, the village of Sa Pa had appeared for the first time on an official map of Vietnam.

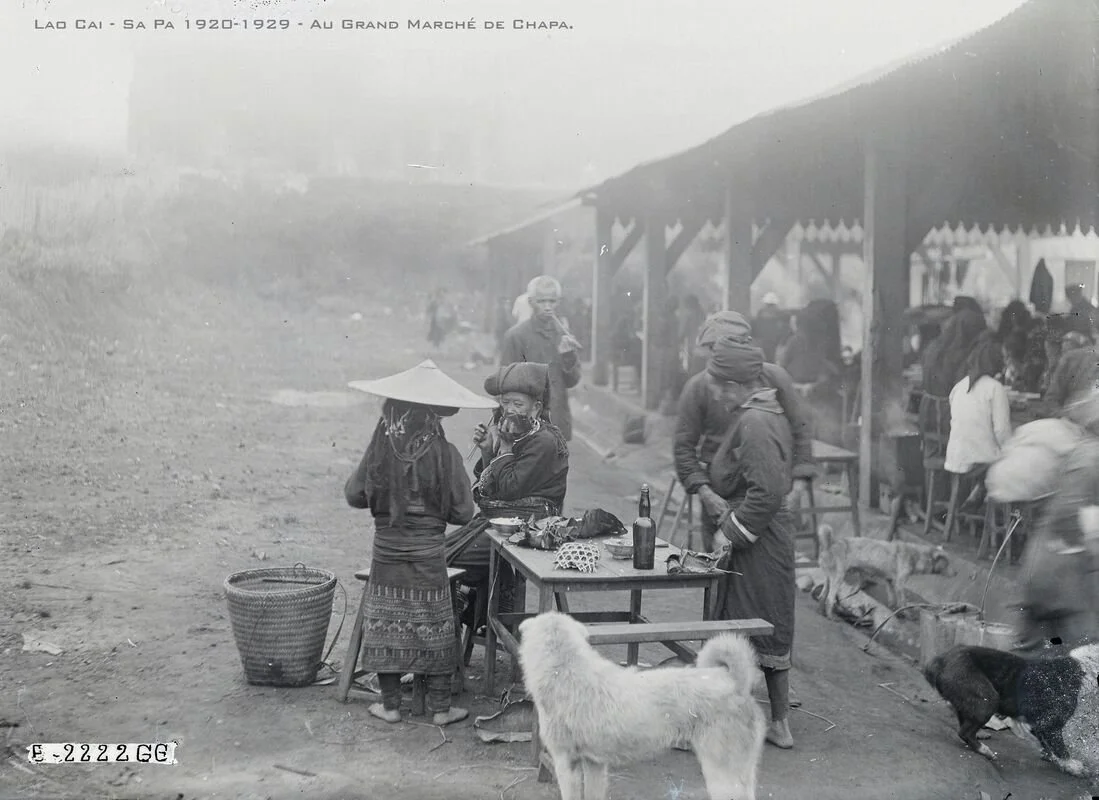

Originally a Black Hmong settlement, Sa Pa first came to French attention in 1901. Two years later, a military garrison was established and named “Cha Pa” (later adapted to “Sa Pa”) after a nearby market village located approximately six kilometres north-east of the present-day town.

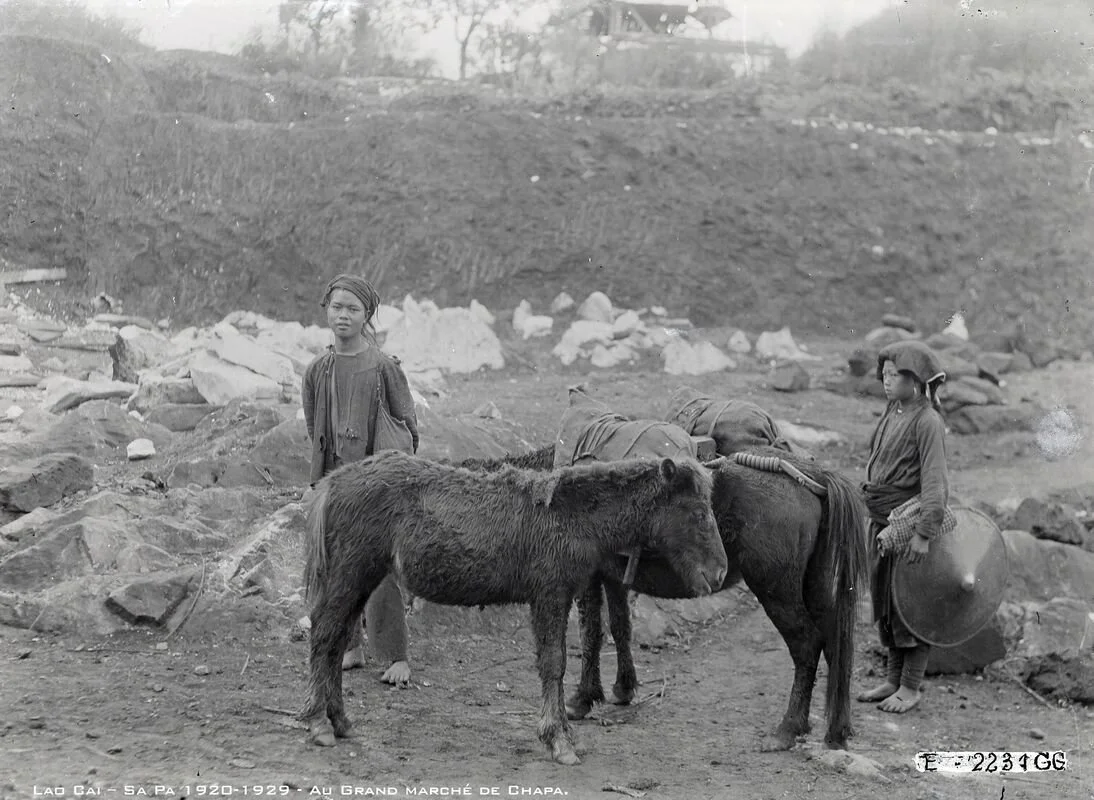

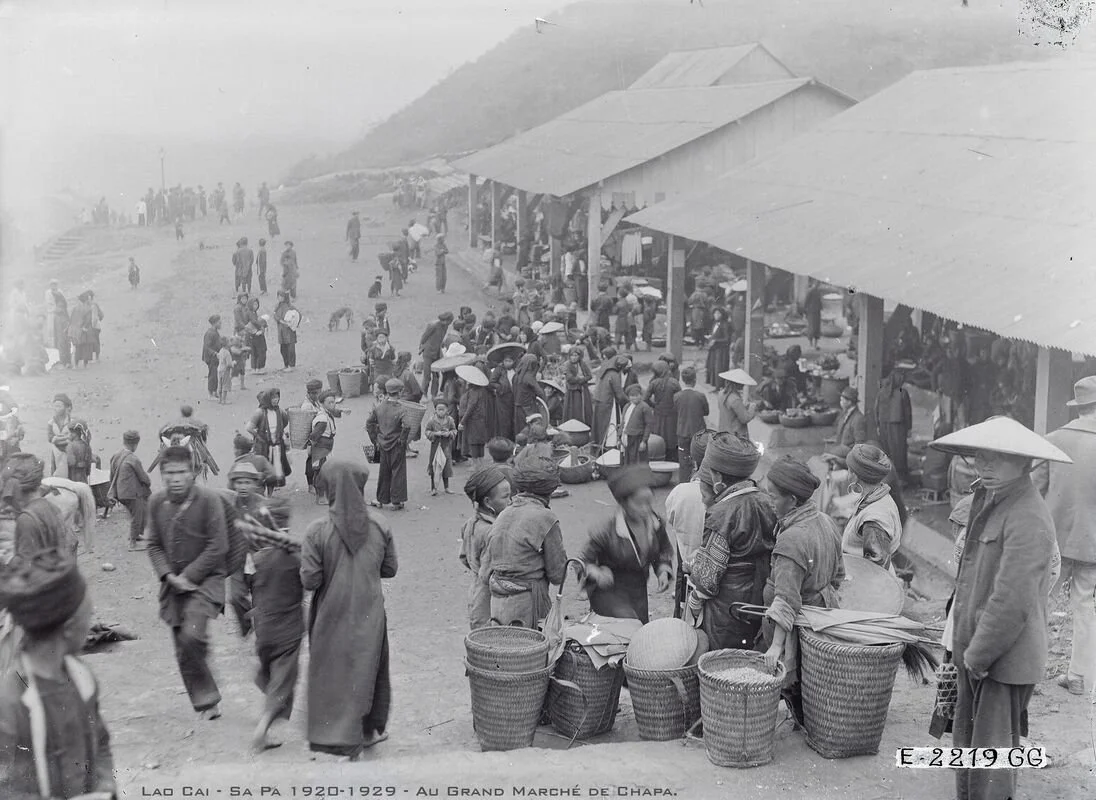

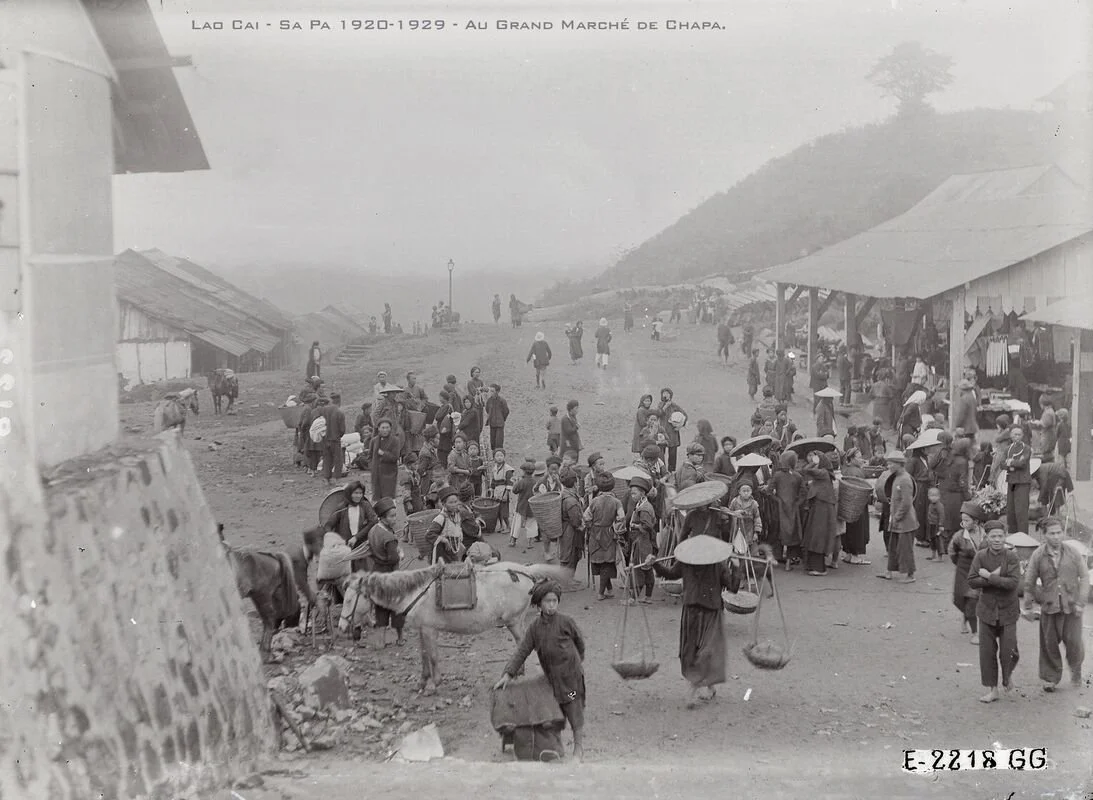

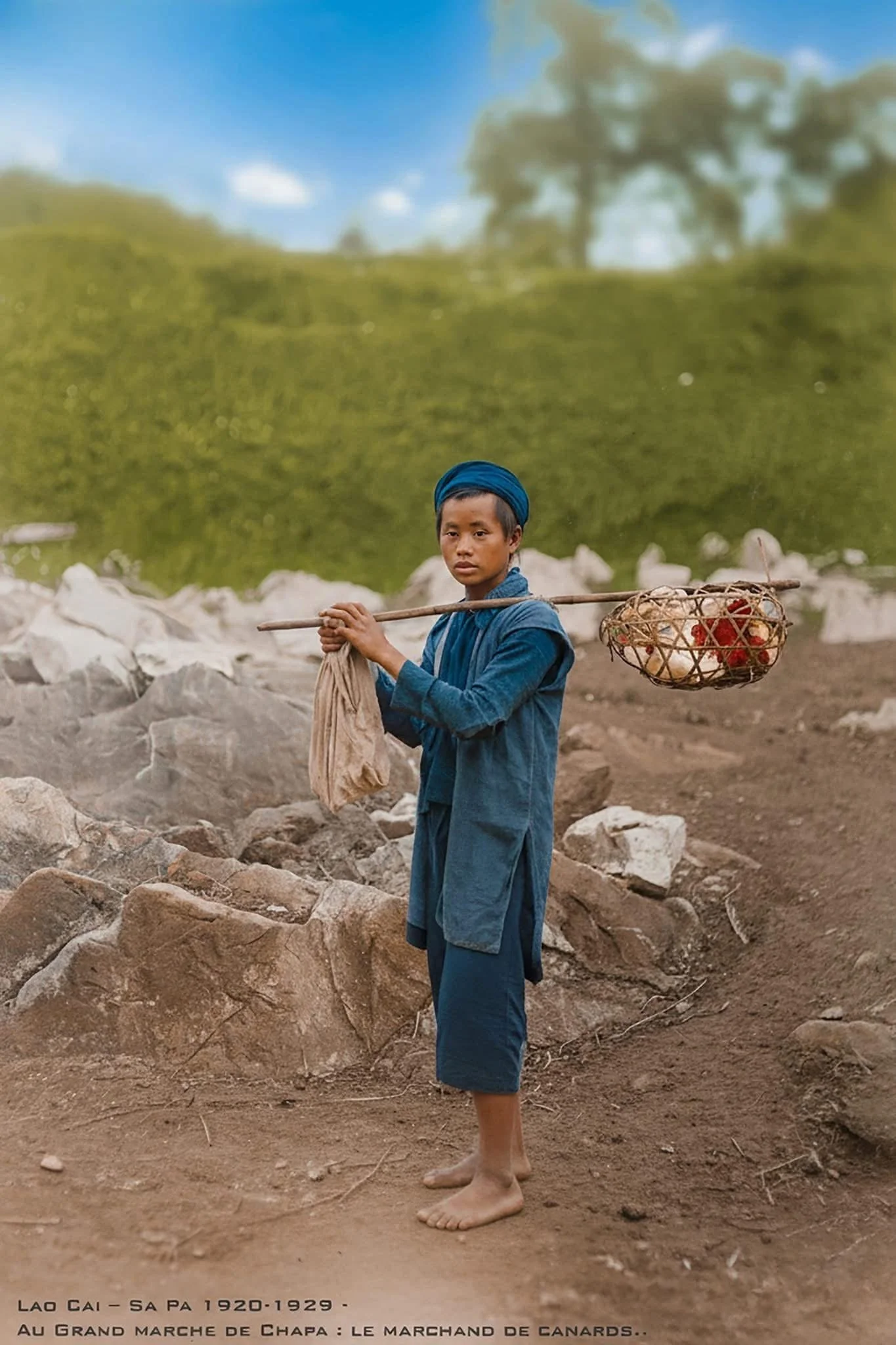

The name “Sa Pa” derives from the Hmong phrase “Sa Pả”. The colonial French tended to call the settlement “Chapa”, reflecting the adaptation of Hmong phonetics into European pronunciation patterns. The Hmong and Dao in Sa Pa communities still preserve many of the customs. If you’d like to experience these traditions first-hand, join us on an immersive cultural journey. [Discover Our Experiences].

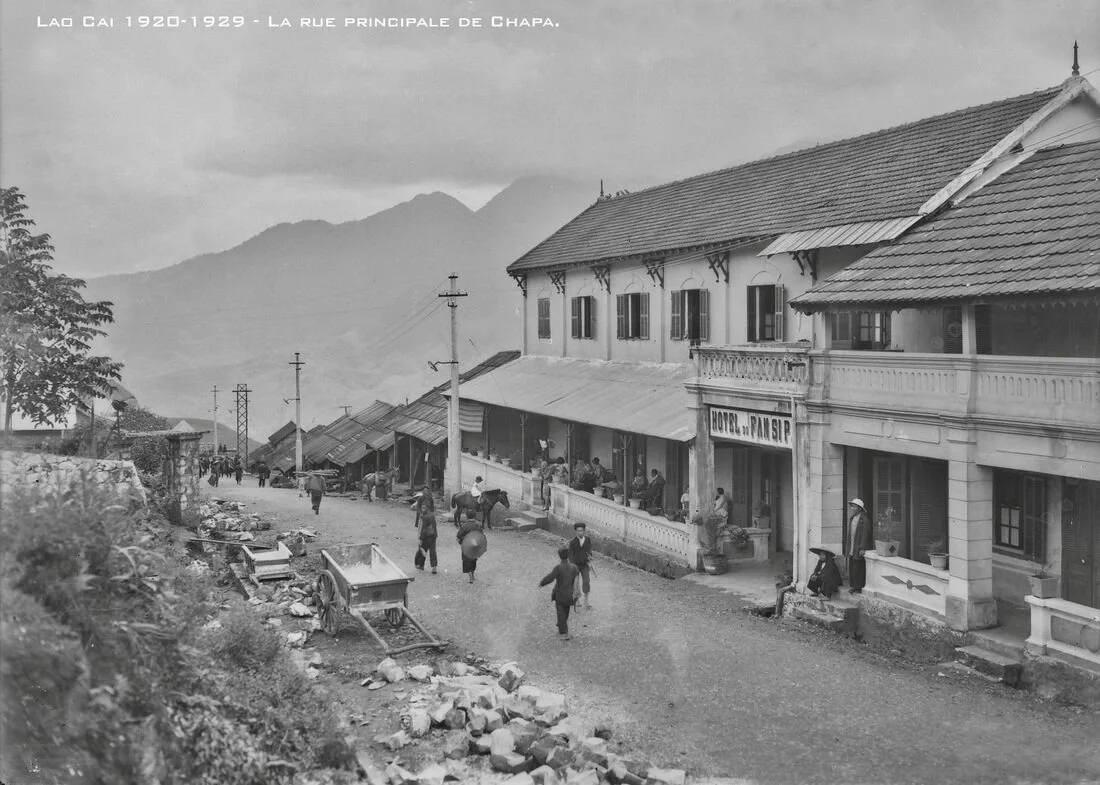

Black-and-white photographs from the early twentieth century record the first stirrings of tourism in the area. In 1917, the French established the town’s first tourist information centre, signalling Sa Pa’s future as a highland retreat. Soon afterwards, the Hotel du Fansipan was constructed on the town’s main road, with several other boarding houses under development. The Hanoi to Lào Cai railway, begun in 1906 and completed in 1920, integrated the town into Vietnam’s rail network. This development accelerated Sa Pa’s transformation, leading to the construction of numerous vacation villas across the plateau.

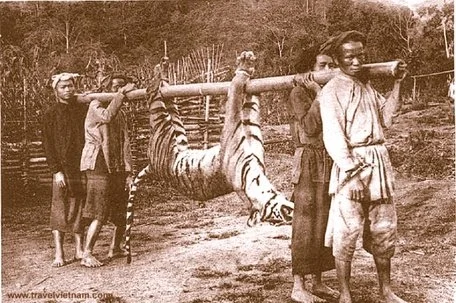

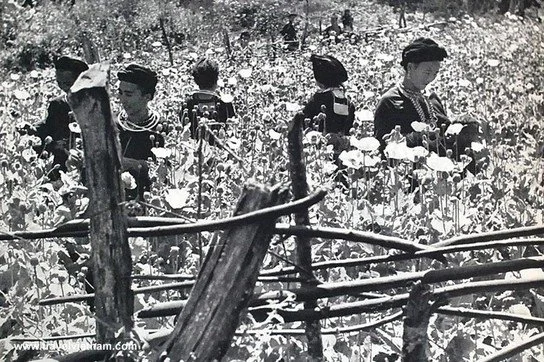

Going further back, during the nineteenth century the Lào Cai highlands were fiercely contested. Armed bands known as the Black Pavilion and White Pavilion gangs, expelled from China after the Taiping Rebellion, sought to dominate trade along the Red River. This commerce included opium from Yunnan, sea salt from Vietnam, rice, textiles, and manufactured goods. Between 1850 and 1886, Lào Cai changed hands several times as rival factions clashed.

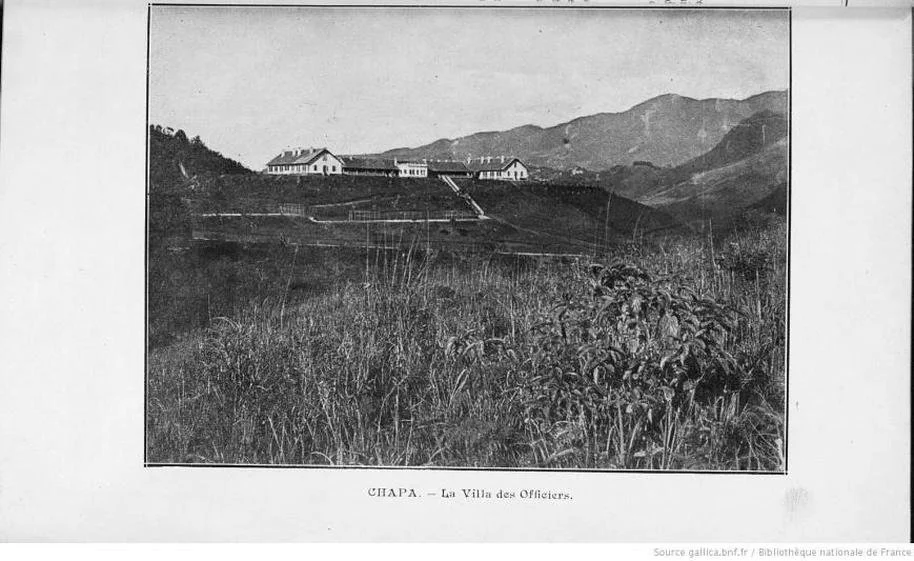

On 30 March 1886, Colonel de Maussion led French forces into Lào Cai to secure the frontier with China and open a trade route to Yunnan. The French sought to outpace Britain in establishing a commercial corridor that would eventually connect with the resource-rich markets of Myanmar (then Burma). In the early twentieth century, Lào Cai became a key centre for controlling the opium trade, which provided a substantial proportion of colonial revenues. Military outposts of the French Foreign Legion were established in Bát Xát, Mường Khương, and Bắc Hà, supported by local militias. French administration of the area lasted until 1945 and resumed from 1947 to 1950.

Before the arrival of the railway, goods were transported along the Red River in slow-moving sampans that carried up to 12 to 15 tonnes, taking roughly 35 days to travel from Hanoi to Lào Cai. In 1898, China granted France the right to build the Yunnan Railway. Construction began in 1901 and reached Lào Cai in April 1906. The 384-kilometre line cost around sixty million gold francs to complete and claimed the lives of about 12,000 Chinese and Vietnamese labourers, as well as roughly 80 Europeans.

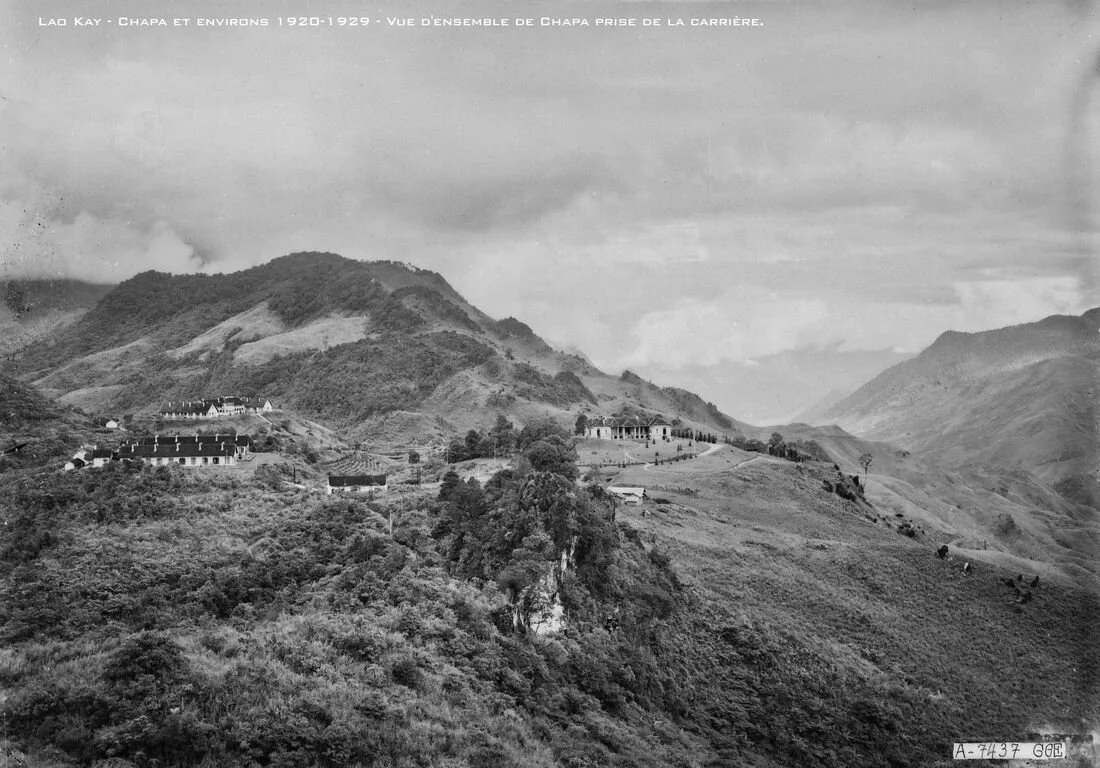

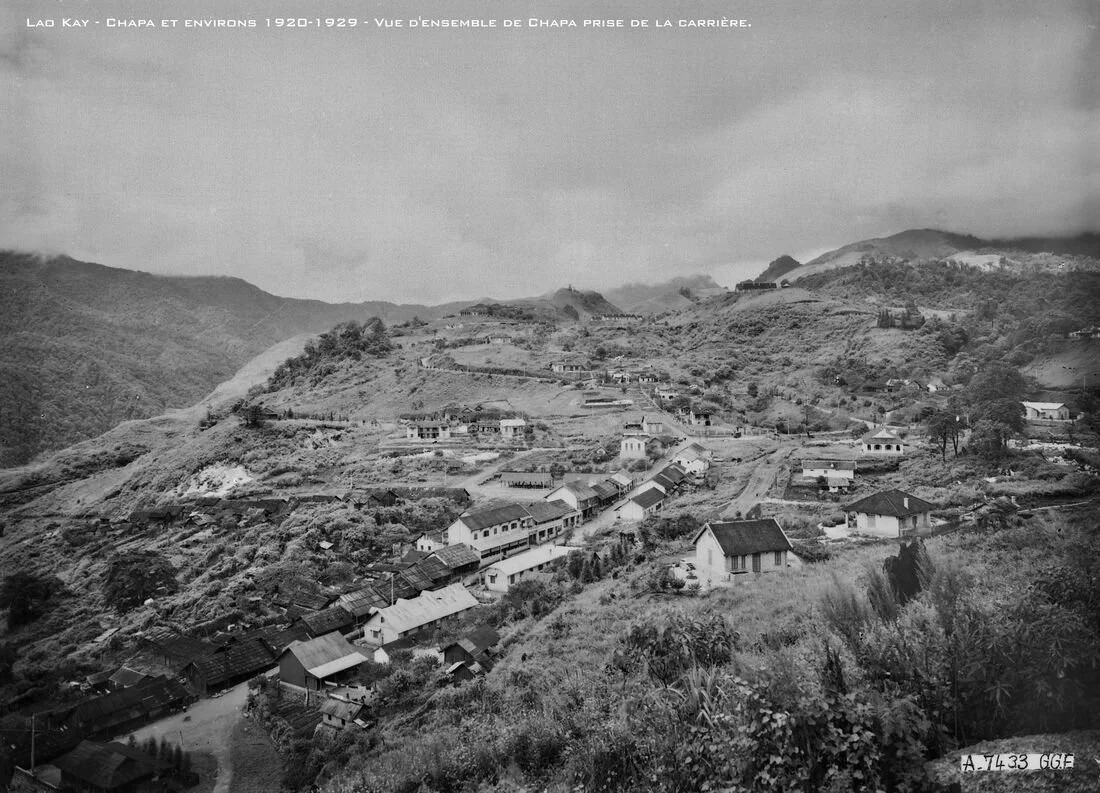

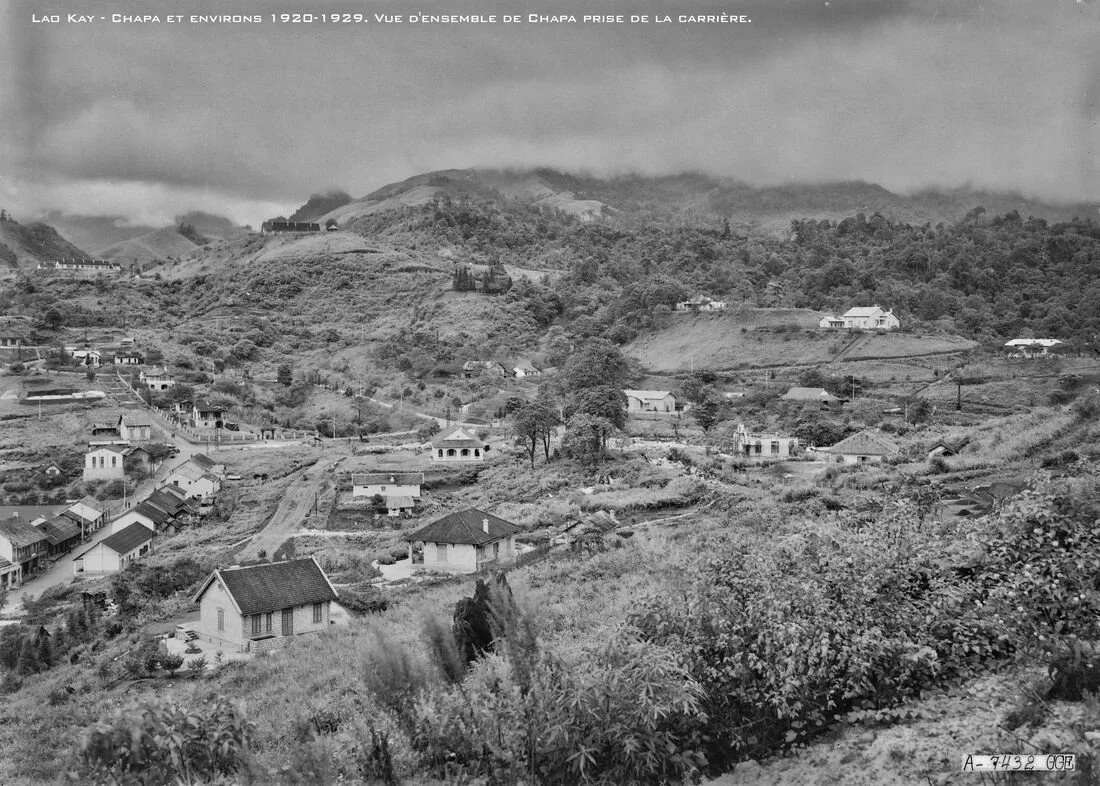

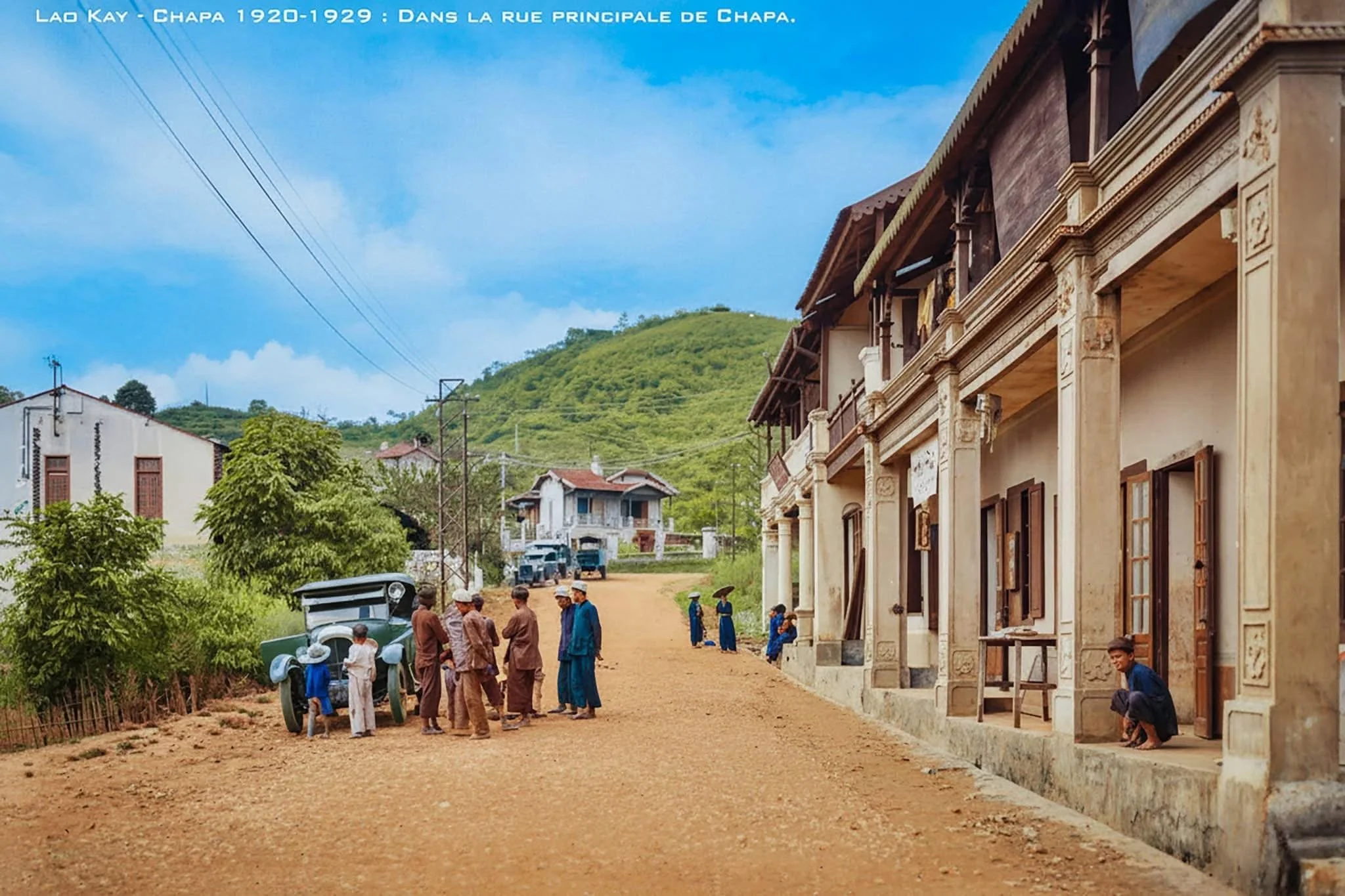

By 1913, a mule track linked Lào Cai to Cha Pa, navigable only on foot or horseback. The road was paved in 1924 and, by 1925, Sa Pa was fully connected to the rail network. Travellers could leave Hanoi at 9 p.m., arrive in Lào Cai after a nine-hour train journey, and reach Sa Pa two hours later, in time for a late breakfast.

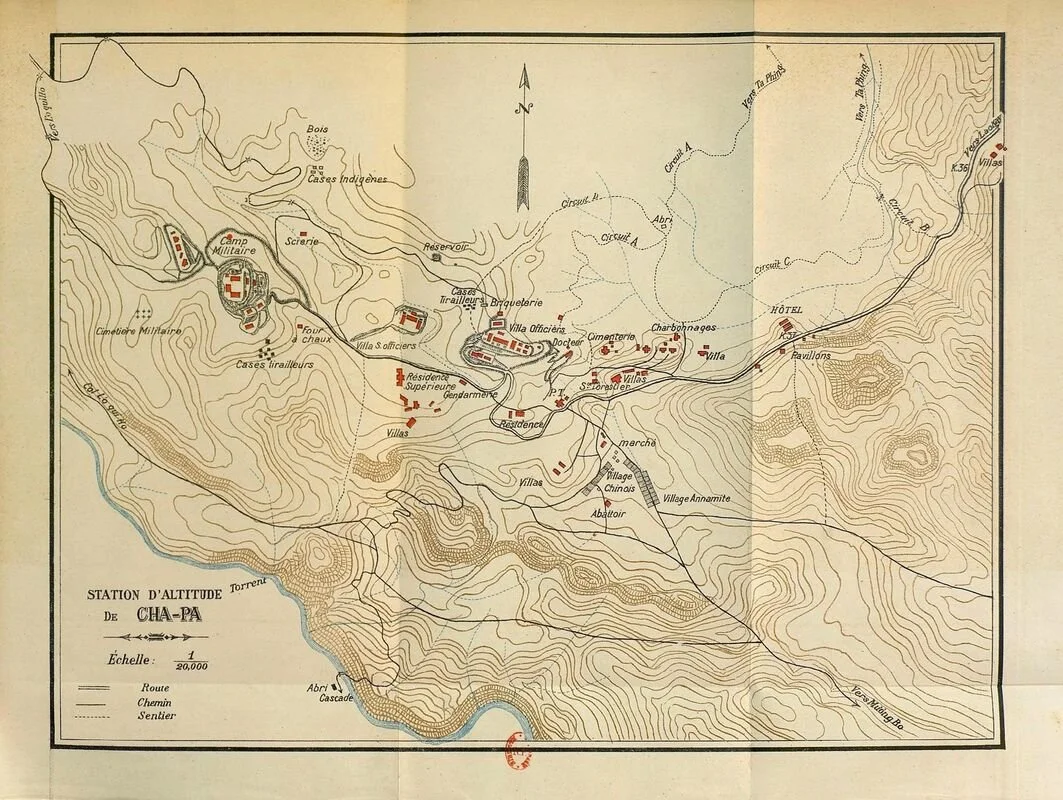

Sa Pa’s plateau was first mapped in 1901, and a French military post followed in 1903. The first permanent Western civilian was Mr Miéville, who arrived in 1906 to work with the agricultural department. Even at its peak in 1942, the French civilian population was only about 20, alongside a small community of English-speaking Protestants of unknown origin.

Initially conceived as a climatic health resort, Sa Pa’s sanatorium opened in 1913 to treat ailments such as chlorosis, post-viral fatigue, malaria, respiratory conditions, and dermatological complaints. The sanatorium occupied a hill above the town and later became the site of the Victoria Hotel, now operating as the Sapa Mountain Resort.

Between 1912 and 1914, French administrators worked to make Sa Pa a “summer capital” for Tonkin. Civil offices were relocated from Hanoi during the hot season, and by 1917 the tourist office was established. Conifers were planted, many of which survive today, and in 1922 construction began on the grand Résidence du Tonkin. Over the decades, several hotels were built, including the Cha Pa Hotel (1909), the Fansipan Hotel (circa 1924), the Metropole (1932), and Hôtel du Centre (1937). From 1918 to 1940, numerous villas were built for colonial elites, alongside the Catholic church (1934) and a Protestant church overlooking the road to Cat Cat.

In 1915, construction began on the Sa Pa meteorological station, the first facility in the region to contribute to the international hydrometeorological network. In 1958, Poland assisted in funding the building and equipping of the Sapa Geophysical Station.

To feed the growing number of visitors, the French developed local agriculture. The Tả Phìn estate produced pork, poultry, vegetables, fruit, wine, and preserves. By the mid-1920s, infrastructure improvements brought running water, hydro-electric power from the Cat Cat waterfalls, telecommunications, and a comprehensive urban plan. By 1942, over 400 building plots had been surveyed.

In 1942 at Tả Phìn, a group of Cistercian nuns established a dairy and farming mission, all that remained of an intended monastery. They cultivated cereals, maintained orchards, and produced butter and preserves for colonial needs. The mission was abandoned in 1947 due to conflict, and the buildings were burned.

Between 1947 and 1952, Sa Pa suffered heavy damage during fighting between the Viet Minh and the French. Viet Minh forces attacked the town in 1947, the Foreign Legion recaptured it, but it was lost again. In 1952, French air raids destroyed the governor’s palace, the sanatorium, and many villas. Sa Pa remained largely deserted until the 1960s and only began significant redevelopment with the revival of tourism in the early 1990s.

French architecture, old villas, and the lingering influence of colonial times can still be seen today, but they reveal only one layer of Sapa’s story. Step beyond the history books and walk with local guides to hear stories that aren’t written down. [Explore With Us]

Hmong and Dao Ethnic Groups During and After the War

During the Vietnam War era, the United States recruited over 30,000 Hmong, and smaller numbers of Dao, mainly in Laos, for the “Secret War” against communist forces. The Hmong served as irregular troops, guiding air strikes, disrupting the Ho Chi Minh Trail, rescuing downed pilots, and gathering intelligence. They suffered extremely high casualty rates, estimated at up to ten times those of American forces. The Dao contributed in support roles, particularly in logistics and local terrain navigation.

After reunification in 1975, the new socialist governments in Vietnam and Laos regarded these wartime alliances with deep suspicion. Many former fighters and their families faced forced relocation, hard labour, and close surveillance.

Behind every historical event are families whose lives were changed forever. Meeting people whose parents and grandparents lived through these times is a moving way to connect past and present. [Meet the Communities]

Ho Chi Minh Friendship Monument in Sa Pa

Today, the Ho Chi Minh Friendship Monument stands prominently in Sa Pa. Presented as a gift to the town, it symbolises the ideals of solidarity, industry, and unity that Ho Chi Minh promoted. Situated near the town amphitheatre and the Stone Church, it remains a significant cultural and historical landmark for residents and visitors.

Modern-Day Sa Pa

Tourism has transformed Sapa, but authentic encounters with nature and culture remain at the heart of its identity. If you’d like to go beyond the busy town and discover the spirit of the mountains, we’d love to guide you. [See Our Experiences]

For years after the war, Sa Pa had little to no tourism. Local residents focused on reconstruction and economic survival, and the town remained largely forgotten. This began to change in 1991, when Vietnam’s policy of economic reform and international integration drew sporadic visitors back to the area. Following the 10th Party Congress in 1991 and the 11th in 1996, Lào Cai Province identified tourism as a key economic sector. Provincial authorities invested heavily in infrastructure, extending the national electricity grid, building clean water systems, paving inner-city roads, and upgrading routes connecting Lào Cai and Sa Pa. Domestic and international tourist numbers subsequently increased.

After its official reopening to global tourism in 1993, Sa Pa quickly became one of Vietnam’s most famous destinations, drawing visitors with its terraced rice fields, cultural diversity, and trekking routes. While mass tourism has brought significant change, sustainable tourism initiatives and community-led projects have also delivered economic benefits, employment opportunities, and cultural preservation for Hmong and Dao communities. In many villages, ethnic minorities now actively participate in shaping tourism policy and practice, advocating for the protection of both heritage and environment.

Today, Sa Pa is a place of contrasts and connections, where colonial legacy meets restoration, the memory of war meets the resilience of recovery, and traditional ways of life blend with responsible modern tourism. The French influence remains visible: the Stone Church, overgrown colonial villas, and European-style cafés evoke a bygone era. French culinary traditions still influence local bakeries, where fresh baguettes and pastries offer a taste of the past.

From architecture to cuisine, perhaps the most enduring French legacy is the way Sa Pa engages with its own history. The town’s past is at once a source of fascination and a reminder of past conflicts. For those trekking through the surrounding mountains, Sa Pa emerges not merely as a scenic retreat, but as a cultural crossroads where art, tradition, and history converge into a narrative of endurance and renewal.

Heritage and tradition must be valued if it is to be protected. Heritage Shorts is our documentary series dedicated to capturing the living traditions of Vietnam’s ethnic minority communities. Each short film offers an intimate look at unique crafts, practices, and rituals that have been passed down for generations. These films preserve and celebrate the cultural richness of northern Vietnam. Together, they form a visual archive that highlights the resilience and creativity of communities whose heritage remains a vital part of the country’s identity.

Sa Pa’s history is written in its landscapes, its people, and its living traditions. The best way to understand it is not just to read but to walk, share, and listen. Let us take you there.